After Janet Malcolm

When Does a Divorce Begin?

Most people think of it as failure. For me it was an achievement.

Anahid Nersessian

1

when my daughter gets out of the car at the airport she vomits, pasta and strawberries plummeting undigested toward her shoes. I place my hand on her forehead; she feels warm; I turn to my husband and say, “Maybe we shouldn’t go tonight.” It’s just before Christmas, and my two children and I have tickets for a 9:00 p.m. flight from Los Angeles to New York. For several weeks my husband has vacillated strangely on the matter of whether he’s coming with us, even though in twelve years together we’ve never spent the holidays apart. When I say, “Maybe we shouldn’t go tonight,” he turns pale and scrubs his hand across his mouth, a gesture I recognize as a personal tell that he’s hiding something. I will later describe this as the moment my marriage ends, but in fact it ends roughly five minutes later when, holding my daughter’s hand and pushing my son in his stroller, their backpacks dangling from the crook of my arm, I walk into the terminal alone.

2

The literary scholar Peter Brooks says that the novel has two plots: the male plot of ambition and the female plot of endurance. Male characters want to do things and female characters want to survive what male characters do. We are trained, Brooks suggests, to associate narrative with either triumph or suffering. But what if a story, a woman’s story, simply went in a different direction, off the rails of what could be predicted or lionized or mourned?

3

For many years I was a success, and then I got divorced. Or, at least, I have been trying to get divorced. The legal case is still pending. In other words, I have been unsuccessfully trying to become a failure or, if you like, failing at failing.

4

My husband and I got married at the office of the city clerk in Lower Manhattan. We didn’t have rings, but after the ceremony we walked to an antique store in the East Village and bought a pair. They cost $250 each; I bought his and he bought mine. If I told you that my ring left a red, itchy welt around my finger, and that my husband’s ring was too big, so it constantly flew off his hand, you might say these things were omens. But they were not a sign of how things actually were, because sometimes we were happy, and often we were content, and for nearly all of the time we were married we were each other’s best friends.

5

There are places in Los Angeles of such surging loveliness and seared grace that they sometimes really do take your breath away—a cliché the city ratifies like it does so many clichés, which are, after all, its primary export. The footpaths that wind through Elysian Park and fling you out, suddenly, to the edge of a cliff over Interstate 5; the rock formations in Agoura Hills, which might belong in Sedona or Santa Fe; the big, dusty intersections that mark the shift from one neighborhood to another, from Koreatown to Silver Lake, from Silver Lake to Echo Park, from Echo Park to Chinatown, from Chinatown to Boyle Heights; the improbable Victorian homes of Angelino Heights and the smoke rising from streetside grill stands; the way the sky dies an electric death every night in October. The years I spent married in Los Angeles I did not see these things. My unhappiness turned the city into a waiting room, a place I could only want to leave.

6

I flirted with a handful of different epigraphs for this essay, and each was discarded in turn. They were about love and lying and speech and silence, and about rights—the ones we have and the ones we wish we had. Epigraphs are envious. They are a residue of wishful thinking: if only we were smarter or braver, our own writing might have begun this way, with an unsparing remark meant to evoke some inarguable truth. They’re also fake-outs. You think this essay, this chapter, is going to take off from them but usually it doesn’t. Usually the real thing, the thing you came here for, toddles in, uncertain. Does any writing live up to its false start?

7

The story of my divorce has no villains. I loaded the gun and my husband pulled the trigger. We were twenty-eight when we met and got married two years later. That morning I’d seen my therapist, wearing what I would get married in, a white cotton nightgown from the Marché aux Puces in Nice. While I was in therapy my husband-to-be bought a bouquet of white and yellow roses for me. I told my therapist I wasn’t afraid to get married because I could always get divorced. She agreed that was true, I could always get divorced. I didn’t do a good job of hiding my ambivalence from my husband, and this hurt him very much. One day he decided that he couldn’t take it; I don’t know the details. We have two children; they’re now nine and four.

8

Not long ago I told B that I wanted to be a kept woman. He blinked coolly. “Who would keep you?” he asked.

9

I did not set out to write an essay on divorce. I was asked to review some books that had come out recently, novels and memoirs, all by women. A few of them had great sentences, but great sentences are compatible with moral vacuity if their author is compelled by little beyond her private experience of the world. Mostly the books were dull, except when they were comically narcissistic or vengeful, worse than vengeful, hateful, vomiting grievance. Even when they were funny they made me feel dim and torpid, as if I had jet lag. I felt annoyed by how recognizable the lives of these women were to me: in nearly every book I read about a book tour, an artist residency, a guest lecture, and I wondered why the women writing these books did not seem more embarrassed by their comfort, or why they didn’t acknowledge that their experiences of divorce—which, on average, causes a woman’s income to drop by 20 percent, whereas men typically experience a 30 percent increase in income—were determined by a very narrow class position, one I share.

If I found myself all too decipherable in these books, I could not empathize with a fear many of them expressed, that if a woman is not a wife she becomes invisible; that the absence of a legible role makes her disappear from the social register. I got married because I was exhausted by being visible: looked at, talked about, hit on. I wanted a life where no one thought about me, where I was protected from other people’s fantasies by the idea that I was now someone’s, off the market of ambient or intrusive desire. I thought I could not look after myself on my own, but when I got divorced I was thrown back onto my own resources only to discover they were not so meager after all. As long as we are talking about what things cost, I will say this: the basic ethical good of divorce—the right to terminate for any reason a relationship that does not suit you—comes with a high outlay, both literally, because getting a divorce is often expensive, and figuratively, because the pain of being open to the world once more is exorbitant. I would pay it a million times over.

10

I was married for ten years, three months, and twenty-four days.

11

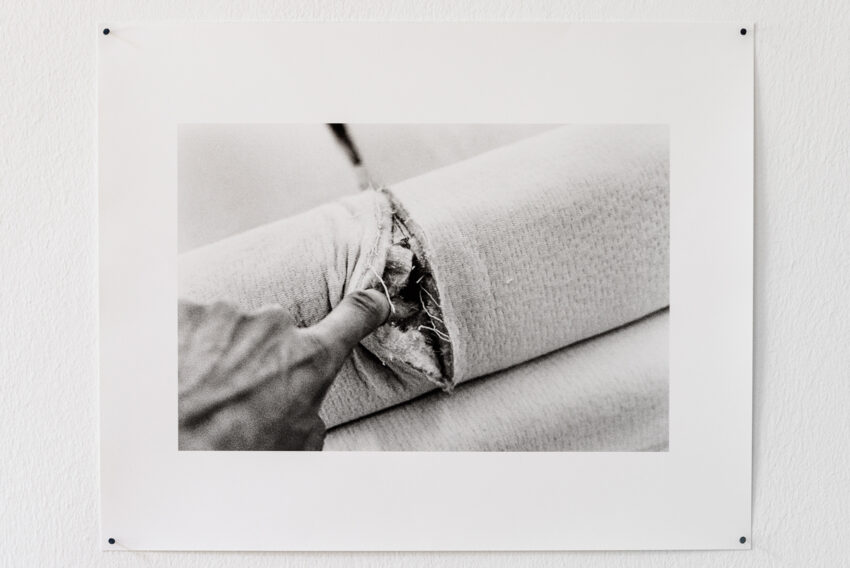

In 2023, the English artist Patricia L. Boyd had a show at Reena Spaulings Fine Art in New York City called Where You Lie. She filled the exhibition space with pieces of a bed, not just any bed but the bed she had shared with her now ex-husband. It was a low bed on wooden slats, the sort of bed you’d imagine an artist having, with a latex mattress and cream-colored sheets. The bed frame had been cut into large sections and its parts carefully staged: the mattress was rolled up with a tangle of bedding set on top of it, a slice of the base was mounted like a shelf, and photographs, some of them taken while Boyd was cutting up the bed, were placed throughout the gallery. In an interview, Boyd explained her inspiration:

The impulse initially came out of personal necessity. While I was going through the process of divorcing my ex, it felt necessary to stop sleeping in the bed we had used as a couple. I wanted to find a new purpose for it, transform its meaning somehow, force an awakening from the bad dream associated with this particular piece of furniture. And the issue of what to do with the bed seemed to have artistic potential, first of all through a consideration of the actions of cutting and separating. Beds are where we lie awake with insomnia or feel safe enough to sleep, where we take our clothes off, have sex, dream, sweat. They’re also where we die.

“A bed is usually a private possession,” Boyd added, “and the act of making it public—to a particular audience—was an important part of that work.”

Because of the pun in Boyd’s title, it is easy to assume that Where You Lie is about infidelity. A bed is a place where people lie down and also a place where people tell lies, a synecdoche for a broader betrayal. But the ambiguity of Boyd’s address—that “you” could be her ex-husband, the viewer, or an impersonal pronoun (“where one lies”), in which case Boyd would be included in its reach—as well as the meticulous look of the installation itself (“I consider it to have been surgery,” Boyd said, “rather than slashing”), shies away from gossip or indictment. Rather, Where You Lie brings to mind a line from Emily Dickinson: “After great pain, a formal feeling comes.”

12

Divorce is a death with no ceremony to mark it. It is a beginning as well as an ending—just one with a mysterious and indeterminate conclusion. If you have children with your ex, you will, as everyone tells you, always be in each other’s lives. If you don’t, your negotiation of finality might be even more complex. What does it look like to come to the end of love, the end of grief, the end of anger? “My husband believed I had treated him monstrously,” Rachel Cusk writes in Aftermath. “This belief of his couldn’t be shaken: his whole world depended on it.” One of the things I found strangest about divorce was the way that, overnight, the condition I shared with my husband dismantled itself. Friends once called mutual vanished. “How are G and T?” T’s college roommate asked when I ran into her. “I lost custody of them in the divorce,” I joked, not joking.

13

When I got divorced people started telling stories about me. A false rumor spread that I was in a throuple with another professor and a graduate student. The rumor circulated only among my professional colleagues and not among my actual friends. It was as if my sex life, freed from the institution of marriage, had to be swiftly contained by another institution, the university. The episode reminded me that to be a divorced woman is still to be what was once called a public woman, a phrase that carries a range of meanings—from “a woman who makes her own money” to “prostitute”—but above all means a woman who is not under anyone’s protection, who exists for others as an object of ambivalent (critical, salacious, aggressive) attention.

I emailed someone who, I’d been told, had repeated the story, and asked him to tell me where or with whom the rumor began. “I’m not going to go any further with this,” he replied, “or involve anyone else.” How fortunate he was, I told him, to be able to make that choice.

14

At a bar in Joshua Tree J and I are explaining what it’s like to be divorced with children. “Sometimes you’re just texting each other pictures of the kids and talking about how cute they are,” we say. “Other times it’s like, ‘This motherfucker.’”

15

I don’t miss my marriage, but I do miss being married. Sometimes I miss my marriage too. Marriage made excuses for me, or rather, excused me. I had a context. In the initial weeks of my first academic job I mentioned to a colleague that I was engaged. His eyes widened. “Oh! I didn’t realize.” I watched myself take shape for him; I was no longer a wild card. My relief, like his, was dizzying.

16

Sometimes when people ask me why I got married I say because I was tired.

17

When I got divorced what I learned was this: a world made by two people can’t be maintained by one. The house fell apart. The boiler broke, handles fell off faucets. There wasn’t any sense in cooking adult meals so I simply stopped eating, or rather I’d eat the crusts left in a pizza box, the buttered broccoli my son refused. For a while I didn’t go out, because I was too sad, and then I started going out all the time. On the weekends when I didn’t have my kids I was twenty-two again, dishes in the sink and clothes on the floor. On the weekends when I had my kids I seemed to do nothing but clean, fold laundry, and drive back and forth across Los Angeles. We went to the beach, a museum, a carnival, a puppet show—anything that got us out of the home that now seemed too big for us, no longer a sturdy support for four lives but a wobbly three-legged stool.

18

Divorce is a writer’s business. You can paint a wedding but not a divorce.

19

In a 2021 review of Susan Taubes’s Divorcing (1969), Leslie Jamison identifies a literary trend she calls “the divorce plot.” If “the traditional marriage plot followed the tangled trajectory of courtship to culminate in the emotional and financial consolidation of a wedding,” the divorce plot “explores the simultaneous grief and freedom that rise from a union splitting along its central seam.” Jamison associates “the traditional marriage plot” with nineteenth-century realist novels, though the best of these—George Eliot’s Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, almost anything by Thomas Hardy or Henry James—focus on marriages that have long since slid into disaster without the possibility of manumission by divorce, which was nearly impossible for the average person.

Among these marriages perhaps none is more painful than the one Dorothea Brooke endures with Edward Casaubon, a sexually inert scholar with a real mean streak, in Middlemarch. When a woman marries for money or social status, as Gwendolen Harleth and Cathy Earnshaw and Anna Oblonskaya do, there’s a good bit of schadenfreude in seeing her eat the consequences. But Dorothea marries Casaubon for other reasons entirely. What she tells her family, and herself, is that she wants to be of use to a neglected genius. Eliot makes us understand, however, that Dorothea actually marries to stifle her own appetite for life and pleasure and beauty—an appetite of which she is ashamed. Love completes us, the old saw goes, but there are plenty of people who don’t want to be completed, who choose a partner to diminish or confine them, to make them less themselves.

20

About a year ago I had a dream. I was in an elevator with a group of people, one of whom had a birthday cake. She asked me to hold it for her, and as she began putting it into my hands it fell to the ground. I apologized frantically, promising to replace the cake right away. I thought, I ruined this beautiful thing that everyone was so invested in. When I woke up I understood that the cake was my marriage. Later I told the dream to my therapist. “What did the cake look like?” she asked. Until that moment I hadn’t realized it resembled the cake we had at my daughter’s first birthday party. In a photograph from the day I am dwarfed by it, which my husband thought was funny. “Why is that funny?” my therapist asked. “Well,” I said, “because the cake is big and I’m small.” She seemed almost angry when she asked again: “Why is that funny?”

21

No one wants you to get divorced and then everybody wants you to get divorced.

22

I never used to notice that the world adults set up for children is a one-party system: two parents in one house. My husband moved out of our house days before our son started preschool, and when the teachers asked for a family photo to share in the classroom I was thrown by the expectation. I went to CVS and printed out two pictures, one of me and my kids and one of them with their dad, and then I sat in my car and cried. When I’d asked S if she ever thought about staying married for the sake of her kids she replied, “I love them too much to make them responsible for my unhappiness.” When I handed the pictures to the teacher I said, “I’m sorry.”

23

With the exception of Nora Ephron’s Heartburn (1983), books about divorce are generally bad and consistently unfunny. This is not because they are about the collapse of formerly loving relationships. On the contrary, the “collapse” parts of these books are usually the best, brimming with the sort of thick description that’s born of resentment and laced with turbulent, incautious humor. They go wrong when they try to narrate their way out of pain and chaos, usually by showing that there’s a happy ending—often in the form of a new partner—on the other side. But while they resemble resolutions, these attempts at closure have the air of false starts. We’ve just been told the many ways it can all go bad. Are we supposed to forget?

24

The way I decided to marry my husband was this: I was living in Chicago, finishing up my penultimate year of graduate school, planning to move home to New York to complete my dissertation. It was June. We had met in March, set up by a friend. He was living above a laundromat in Alphabet City and going to grad school too. He came to visit me, and then he came to visit me again. The idea was that I would teach my last classes before the summer break, pack up my apartment, and drive back to the East Coast with him. But when I picked him up from the airport that June I had a fever, and then I got very sick, because this was a time in my life when I couldn’t be bothered to get a flu shot. Over the next couple of days he finished packing for me, sold my couch on Craigslist, and heated soup and made me toast. We watched the entire Godfather trilogy, and then he drove us the eight hundred miles to Red Hook, Brooklyn, where I was taking over a friend’s lease. I decided to marry him because, on the drive, I never felt bored, and because I felt safe, and cared for, and like it was possible to be loved without also being in pain.

25

In an interview with Vogue magazine last year, the novelist Sarah Manguso said she had “discovered,” since her divorce, “that infidelity is highly correlated with coercive control and domestic violence, and virtually everybody who has committed an act of mass murder has preceded that act with what we call domestic violence, which is men abusing women physically and in every other way.” Manguso referred to her own marriage and her novel Liars, which depicts a marriage with remarkable similarities to her own. I took a screenshot of the line I’ve just quoted and texted it to some friends. “I guess I will not be reading the new Sarah Manguso,” I wrote. But then I did.

Over the course of my romantic life I’ve cheated, been cheated on, and occupied the role of that stateless person, the other woman. The circumstances of my own divorce involved a combination of these experiences too convoluted (and too personal) to describe here. There were obvious and less obvious forms of betrayal, and all of them hurt, though I can’t correlate any of them with abuse, let alone understand them as predictors of mass murder. Infidelity means faithlessness. When we marry, what is it we place our faith in? Ideally, in the belief that our partner will always have our best interests at heart. More often, in the belief that love entails obligation, that if I love you, you are in every quadrant of your life responsible to me. There are people who love mainly because they want other people to owe them—to be under an obligation to always be loyal, sincere, consistent. This is a very depressing kind of arrangement.

26

Marriage is a panic room, a safety lock, a stable for one, a conspiracy of two, a compromise and compulsion, a moonshot, a white flag, red tape, no accident, a desert island, a private language, “a human Society” (John Milton), “a stupid endless mistake” (Delmore Schwartz), “like you say everything everything in stereo stereo” (Anne Waldman), a bird in the hand, a cut corner, a plea, a bargain, a violet hour, a path of least resistance, a tonic, a toxin, “close to the target, very near” (J. H. Prynne).

27

Only my daughter can remember a time when her parents were married. My son, who is four, knows his father and me as two separate people, not the mommy-and-daddy unit my daughter used to call for when she woke up. There is a video of her announcing to my parents that she’s going to have a baby brother; her eyes are shining and her little body shivers with joy. And then she says: “This is the big news. I am going to make his room, with Mommy and Daddy.” Now, whenever my son is with us both at the same time, he takes us each by the hand and says, like he’s getting away with something, “Mommy and Daddy, ha!”

28

People think divorce is a failure. For me it was an achievement.

29

In her landmark 1988 book, The Sexual Contract, the feminist political theorist Carole Pateman argues that contract theory, which emerges in the political writings of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thinkers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, represses an important aspect of the contract people make with one another in a civil society. The contract is not formed out of a consensual relationship, such as that between citizens and their sovereign (as Locke and Rousseau argue); rather, it comes out of the essentially nonconsensual relationship between husband and wife. Nonconsensual, that is, because under the conditions of early modern patriarchy, a woman was not considered to have what Locke calls “a property in [her] own person,” which means she could not freely consent to give herself away in marriage, since you cannot give what is not yours. Pateman’s insight is that our seemingly consensual contracts are, at heart, nonconsensual ones. Society begins when at least half of us eat shit.

30

My husband and I conceived a pregnancy the first time we tried and shortly thereafter lost it. At our ten-week checkup the ultrasound showed nothing but an explosion of cells in a strange formation that my doctor told me could be a sign of a very serious cancer. On the morning of my D&C I asked if I could listen to music during the procedure and the doctor said yes, lots of people do that. I put on my headphones and chose a song that reminded me of an ex I had seen at a friend’s wedding not long before. I had talked myself into the idea that seeing him one last time, for a closure we did not then achieve, was a good thing to do before trying to get pregnant. It would set things right in my soul, make it a good home for the love of a child. As I lay there dimly hearing the buzz of the machine removing dead tissue from my body, I tried to shuffle one pain into the other; it seemed more bearable that way. At my friend’s wedding I had read some of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s description of the Lovers card from his book on Tarot, where he writes that if the card could speak it would say:

I permit you to live your own life and assume your own light and beauty. In the heart where I dwell, I drive out the illusions of the unloved child. Like the bell tower of the cathedral, I spread the penetrating vibrations of love in your blood, stripped of all resentment, all emotional demands that have become a travesty of hatred, and all jealousy, which is only the shadow cast by abandonment. I initiate you into the desire of obtaining nothing that is not also for others. The island of the ego is transformed into an archipelago.

When it was over the discharge papers described me, in a clerical error, as three months pregnant. I folded them in half and shoved them into my pocket. Later I asked my husband if we could get in bed and watch movies for the rest of the day. I watched and he read a book by my side, easily tuning out the television.

31

Complaining about his current partner, a man I used to love concluded with the pious reflection that he could not wish to have chosen anyone but her, because then he would not have his children, whom he adores. Well, I thought at the time, if you’d had children with someone else, you’d love them just as much, and their existence would be as singular and imperative as your children’s existence seems to you now. But people are very attached to the idea of having no regrets, and to exonerating their unhappiness by pointing out its upshots. We want to believe that none of our starts have been false, that we have progressed, sure-footed, toward what was always going to be and so could never have been refused.

32

When it was clear we weren’t going to stay married my husband and I started meeting with a couples therapist. The sessions felt as perfunctory as a trip to the DMV. In response to anything my husband or I said the therapist would offer some version of the phrase “There’s a lot of hurt here.” After we’d gone four times we received emails explaining that the therapist had suffered a heart attack; she would no longer be seeing us as clients. I liked to joke that she could tell we were a lost cause, that all three of us were wasting time.

33

On the mornings when I have my children, I make lunch and snacks, give them breakfast, and help them get dressed. My son will ask, “Who’s picking me up?” And sometimes when I say, “I am,” he wants Daddy. Sometimes when I say, “Daddy is,” he’ll grin and shout, “Hurray!” I’ve learned to act as if this doesn’t bother me, and some days it doesn’t.

On the mornings when I don’t have my children, I try to sleep past 6:00 a.m. but rarely do. Instead I lie in bed and listen to the house be quiet.

34

“After the day’s work was done, Ma sometimes cut paper dolls for them.” I am reading Little House in the Big Woods to my daughter a few weeks after her father has moved out. “She cut the dolls out of stiff white paper, and drew the faces with a pencil. Then from bits of colored paper she cut dresses and hats, ribbons and laces, so that Laura and Mary could dress their dolls beautifully.” My daughter is sleepy, the world of Laura Ingalls Wilder hypnotically alien to her. “But the best time of all was at night, when Pa came home.”

35

When I was married I wanted to leave Los Angeles, and when I got divorced I decided I never would, no matter how many fires burned there.

36

One day about a month after my husband moves into his own apartment my daughter goes missing at school. I’m there at the usual time and she’s nowhere to be found. The playground staff call for her on their walkie-talkies. A couple of people are sent to look for her. I am told to wait outside the school’s entrance. Ten minutes pass, then fifteen. My son starts to fuss in my arms, sensing that something is wrong and knowing from her name crackling over and over again on the walkie-talkies that it involves his sister. At twenty minutes I call her dad; at thirty-five minutes he has rushed to the school from his apartment. I have been seeing someone for the last few weeks and I feel my whole being swing toward him, but I go and stand next to my husband, distantly aware of the sensation of my trust anchoring elsewhere, away from the only other person who cares as much as I do that our daughter has disappeared. Like those robot toys, Transformers, we form a single parent mass, a mass without romance or rancor. We are standing next to each other in the thought of our child, who is found, at forty-five minutes, playing chess with her teacher in a classroom no one thought to look in. When she sees how scared everyone is she almost starts to cry. Her dad and I hug her at the same time, tell her no, she’s not in trouble at all.