I was sleeping with a man who described his marriage as ailing. One night, when I was talking to the man on the phone, he recounted a time when he had gone, with his wife, to a party. He had clinked beers with the host and said, “Sorry we’re late. I’m in the doghouse.” The host snorted, gesturing at the man’s wife, and replied, “Dude, you live in the doghouse.”

The man described his wife’s mean streak, her disordered eating, their vanilla sex, and her habit of absentmindedly picking her teeth. Even though I wanted to hear it, I thought it was cruel. It was unnecessary if the marriage was on its last legs. The doghouse sounded like asylum. I wondered what it felt like—to be in the doghouse, to walk around and go to parties with his wife. How bad could it be? There was probably TV and nachos and Wi-Fi in the doghouse. There was beer.

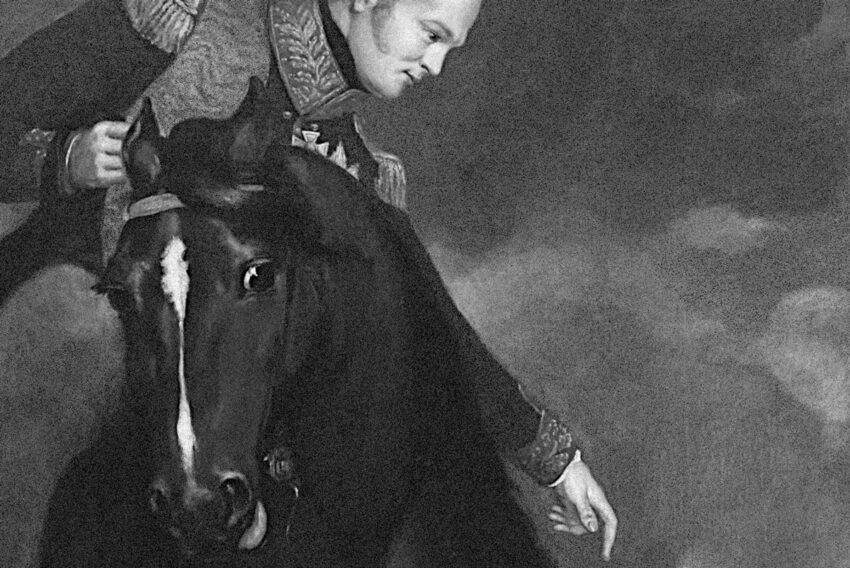

There is a large painting that hangs in the main stairwell of Chandos House, a building once occupied by the Royal Society of Medicine. I would stay there when I was in London. It is a depiction, in oils, of the moment when Emperor Alexander I of Russia, on horseback, beheld a peasant who had been pulled from the water. From his saddle, the emperor reaches toward the sodden man, whose skin is painted the same white as his shirt. He is being propped upright by three men, their faces dark with pleading and with fear.

The plaque reads: The Emperor, seeing the apparently lifeless body of a peasant which had been dragged from the River Wilna, dismounted from his horse and, after more than three hours’ constant personal effort, succeeded in restoring the man to life.

I asked the man why, if the marriage was in fact over, he did not tell his wife he was in love with another woman. “It would obliterate her,” he said, and then he quoted Hippocrates: “Do no harm.”

I thought this over.

The man told me he was spending nights at his father-in-law’s beach house while he and his wife were separating. He sent my child books that his own children had loved when they were small: one about a giant jam sandwich, another about moles. These books arrived in the mail; my son enjoyed them.

He told me that in the water opposite his father-in-law’s beach house, one hundred and fifty years after Alexander I resuscitated the Lithuanian man, a woman had drowned. He described the wind making a fine grain on the surface of the water at the spot where the drowning occurred.

When he visited me, the man did not wear his ring. But once, on a video call, I saw a glint on his left hand. “Oh, I’m wearing it for Marco,” he said. Marco was a colleague of his wife’s. “I saw Marco tonight, and I want to protect her dignity.” Then he took it off in a show of something.

One night, as the man was speaking to me, his wife came into the room, grabbed his phone, and hit him on the head with it. I listened for a few moments, then hung up. I looked up the oath. I copied and pasted one section of what I’d found into a text to the man: I will follow that system of regimen which, according to my ability and judgment, I consider for the benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous.

He did not reply or return calls. I became agitated as two days passed. I was impatient with my son. I sent the man another text, one I thought might be less ambiguous. It was from an older version of the oath that had since been amended: I will give no deadly medicine to anyone if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and in like manner I will not give to a woman a pessary to produce abortion.

Later that afternoon, while I was riding the subway, a woman sitting across from me started shaking violently. Her eyes rolled back; she slid off her seat and onto the floor as the train slowed, pulled into a station, and stopped. Her straight black bangs swung from side to side. A passenger rushed in and cradled the woman’s head to keep it from banging the floor, and another ran for help. I asked if there was anything I could do. “No,” the passenger said. I left the car, glancing back through the subway window at the shaking woman, wildly animated but insensate. She and I looked to be the same age, and I shuddered, thinking it was supposed to be me, thinking of the pre-Hippocratic belief that God smote sinners with seizures. That they were “cured” by incantation. I needed an incantation. As I walked the extra blocks home, I repeated: Do no harm, do no harm.

On the third day, the man called and explained that he had checked himself into a psychiatric ward. “I was worried I would hurt myself,” he said. “I want to spend the rest of my life with you.”

When I looked it up, years later, it came as a surprise to me that there was no relation between Hippocratic and hypocrite.