In Objects of Desire, a writer meditates on an everyday item that haunts them.

My Rosary

A priest from my childhood was convicted of embezzlement. Years later, he still informs my faith.

Nicholas Russell

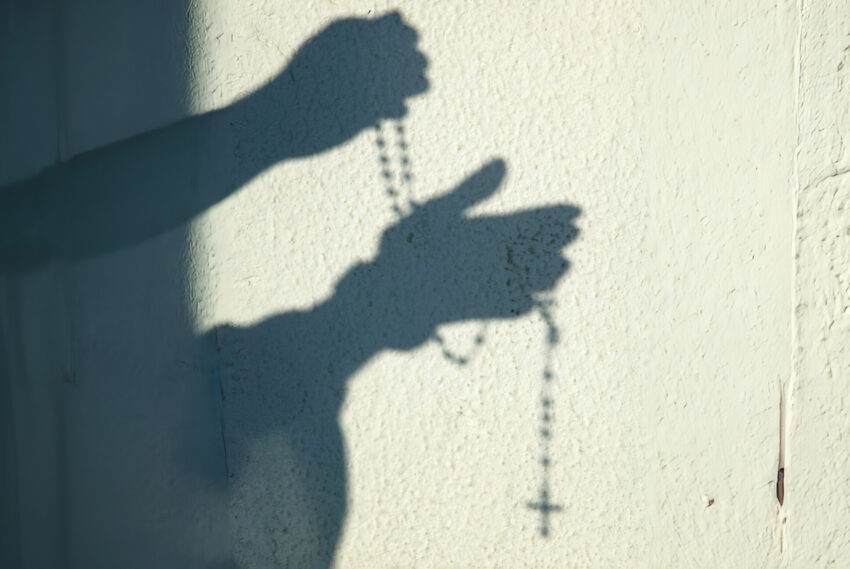

My rosary: pitch-black beads, each puzzlingly slick, like greasy fingers have handled it, held together by an intricately woven silver chain, a lovingly sculpted silver crucifix trailing the end. It has heft, not like one of those cheap ones, with craft beads that could as easily be from promise bracelets or animal toys. It feels like it was made before mass production—before trash. When I first saw it in the parish gift shop, my hunger for it was almost sinful. That was before I knew what religion had to do with money. Before I knew some people grip their faith so tightly because what lives in their hearts exceeds their or anyone’s grasp.

In Catholic school, you had to look the part. Our dress was uniform, obligatory, without much room for personality. Perhaps that’s not surprising. Private schools, religious or not, make you carry the weight of expectation, of isolation from the rest of the world. My school was in an upscale neighborhood in Las Vegas and one of the largest Roman Catholic congregations in Nevada. For most of its history, the church’s parishioners were almost entirely white. It was a place where you could still buy your way into heaven.

Our priest, Father K, was tall and slight, with crooked teeth and a beat-up Cadillac that he seemed to drive only to Mass. He wore the usual priestly garb (clerical collar, button-up black shirt, black jacket, black pants) but in a way that seemed to embody a rugged asceticism. His black shoes were beat-up boots; his black pants were dusty jeans. Looking at his bony shoulders, I would wonder if he ever ate anything besides the Eucharist.

I remember thinking that he took things way too seriously and that such a serious person was not capable of being remarkable.

I’m not sure if Fr. K was much involved with the school. Our classes weren’t taught by priests or nuns. We had professional teachers attracted by the veneer of respectability and the supposed ease of work. But they soon discovered the strict oversight applied by the administration and the small army of parent volunteers who roamed the halls. Their work consisted largely in reminding students to keep their shirts tucked in; the ones whose hearts weren’t really in it didn’t last long. Mr. V, who taught fourth grade, forwent the curriculum most days and let us play a classroom version of Jeopardy! instead. Mr. H, who taught science, once told the class to “shut the hell up” and broke down in tears when we didn’t. Ms. T, who taught English, was an atheist and told us so.

We rarely saw Fr. K around campus. One privilege of being a priest was that no one paid much attention to him. He was withdrawn, shy, and so boring that few thought of intruding on his solitude. Not that all the priests were like this. Fr. P rode a motorcycle and wore a leather jacket. Fr. F rushed through mass as if he had somewhere else to be. They both attracted more attention from the half-interested majority. But for the devout, Fr. K was the real deal: earnest, severe, withering in his disdain for those who lacked belief or strayed from the faith. I remember thinking that he took things way too seriously and that such a serious person was not capable of being remarkable.

Three years after I graduated and four after I bought my rosary, Fr. K went to prison for embezzling almost $650,000 dollars from the parish gift shop and prayer funds to support a gambling addiction. It must have been easy while it lasted: he was the signatory for the parish’s financial statements and had complete control over the flow of money. Anyone might have been tempted; it’s not hard to imagine this lonely, privately afflicted priest giving in. More than a few parishioners went to bat for Fr. K. One woman wrote the court, “I speak for myself and many from our very large congregation, that we are sorry for what Fr. K has done, but all the good that he has done for all of us over these many years has outweighed the sin of taking the money from our church."

It was a common assertion that Fr. K had been living a double life, that his public identity and his private crimes were deliberately kept separate. His attorney said that Fr. K, along with his addiction, suffered from anxiety and depression, that he had been a pillar of the community, that he had been going to treatment. In response, the prosecution claimed that Fr. K hadn’t once touched his own savings during his embezzlement.

The church wouldn’t be nearly as interesting without its finery, its concern for appearances, its greed.

It’s a seductive thought, the hope that stealing from the modest gift shop and the little pile that accumulated every Sunday wouldn’t be noticeable. When my rosary, before it was mine, caught my eye, there was nothing but God to stop me from taking it then and there. Fr. K could have had access to a much larger pool if he had dipped into our tuition. But there are advisory boards and credentials managed by officials for that kind of thing. Among committees and officials, there are other histories, other crimes, other testimonies. For the secret accounting of the self-effacing, deeply indebted priest, there was the gift shop and the offertory basket.

There are fifty-nine beads on a rosary. In Isaiah, chapter 59, it says “we are well aware of our guilt.” Fr. K was fifty-nine when he went to prison.

I came across my old rosary recently. As it happens, I rarely used it after I bought it from the gift shop. Its value was tied up in who saw me with it, not how long, how faithfully, it would be used. That strikes me as a very Catholic thing to think. The church wouldn’t be nearly as interesting without its finery, its concern for appearances, its greed. It might have been this preoccupation with surfaces that allowed Fr. K to evade suspicion. It reflected away any association with greed, made parishioners take his aloofness and his seriousness at face value.

Fr. K didn’t die or disappear, even if it felt that way. If anything, I was the one who changed form, getting older, losing my faith, getting it back, getting a job. Our parish, too, transformed several times over, with new churches, new priests, a new bishop, many new parishioners. My old school, as I knew it, can feel so far away, even though I live right down the street.

The bookstore where I work is on the other side of town. Not long ago, Fr. K came into the store. He looked much the same, still lean, if slightly diminished. I can’t imagine what it must be like to go to prison and to come back out. He looked exposed, even after all this time, clear across town from the scene of his crime, as if the people around him could tell by sight what he had done. Not quite glancing over his shoulder, but alert, furtive, out in the unsupervised open. I suppose his fear of being recognized came true when I saw him, though he wouldn’t and still doesn’t know it. In my anonymity to him, I considered how I felt. For a long time, I thought I hated him. The severity of his transgression made my response simple. But the crime, proximate though it was, really had nothing to do with me or my friends or my family. My hatred was from somewhere else, on someone else’s behalf. It was for appearances, even if it was only for myself to see.

Meaning is elastic, most especially the kind that forms around people, individuals, figures who hover nearly invisibly in the periphery of one’s life, maybe hold some authority, like the moral example of a priest. I remember being frightened not of Fr. K but of what he embodied: the impersonal, cold, punitive instincts of a man who believed that the church, whose love I have been lucky to discover despite this uncertain beginning, must be hard, unwavering, even cruel. After he left the store, I looked him up. He is still a priest, though at a different church and in a position with little power. His new church is in Arizona, at a Byzantine Catholic Church in a major city. Actions, gestures, intimations fill my thoughts, my prayers. I pray for his health, his safety, his confidence in whatever permutation of his life he comes to embrace. I touch the beads of my rosary, remembering the time Fr. K blessed it. I still consider it sanctified. We are well aware of our guilt. What comes next?