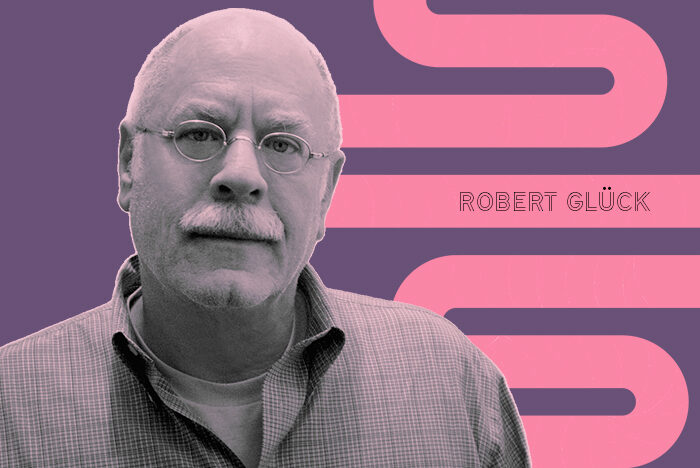

The writer Robert Glück has long been a central figure in experimental and queer literature. He first came to notice in the 1980s with Elements, a book of stories, and Jack the Modernist, a novel about the relationship between two gay men that conveys their romantic and sexual connection using striking, unconventional language. Glück’s influence deepened as he worked alongside writers such as Bruce Boone, Dodie Bellamy, Kevin Killian, Steve Abbott, and Camille Roy. Together, they formed the New Narrative, a San Francisco–based artistic movement defined by fleshy, unflinchingly candid, and formally exciting writing.

In recent years, Glück has reached a wider audience through publication with New York Review Books. In 2023, NYRB published Glück’s best-known work, About Ed, his acclaimed novel about his relationship with the artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai. NYRB republished Margery Kempe and Jack the Modernist, bringing his early work to a new generation of readers. I corresponded with Glück over email, discussing Jack the Modernist, About Ed, and writers and lovers who deserve to be remembered.

—samuel ernest

samuel ernest Jack the Modernist was reissued this fall by NYRB. I’m so glad this has happened. For years, I searched used bookstores for a copy of the edition published by High Risk, and I finally found one for $4.95. Copies often go for more than a hundred dollars online, which speaks to its status as a cult classic. As you revisited the text in advance of this reissue, did your thinking about it shift? Did you make any changes to it?

robert glück It was an odd experience to reread the text after thirty years. I had had an opportunity to make changes when Jack the Modernist was first republished in 1995, just as I’d had an opportunity to make changes to my novel Margery Kempe when it was reissued in 2020. To my surprise, in both of those instances, there was almost nothing to do. The completion of those books meant that I had become the person who wrote them. In some way, they are a record of change. I suppose I can make the distinction between finished and resolved. There are gaps in my books, incommensurates built into their structures, but that does not mean they’re unfinished. I want emptiness, silence, and the unknowable to travel along with the story.

There was one word I needed to change. When I described Minnie Mouse, I mentioned her “stylish shoes.” I should have called them pumps! That troubled me for decades, an unforgivable sartorial lapse of homo appreciation. Speaking of Minnie, she appeared in the image-essay that went through the original 1985 edition of Jack. When the book was republished in 1995, my publisher, High Risk, wanted me to secure rights for the images. I got ahold of a Disney executive and carefully explained: small press, literary book, experimental, small readership. He replied along the lines of “We’ll break you.” I had to let Minnie go. But early Disney images just entered the public domain, so Minnie has returned to my book in glory as the frontispiece. Jack is partly a portrait of the gay left of that era, so there are plenty of comparisons with contemporary politics to be made, battles won, battles still to win, new battles to be waged.

Beyond that, I’m surprised by what a brat I was then—the term at the time would have been “attitude.” And variations of “cock” appear sixty-two times. My goal in writing Jack was to create a feeling of risk, of the irreversible, that the reader shares with me in a performance where I make myself naked. So, it’s a surprise to happen on my naked self, circa 1985. I made tiny changes but nothing to alter the excess at the heart of the story.

SE Although Jack is your first novel, many new readers have discovered you through About Ed, your book on your relationship with the artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai, who died of AIDS in 1994. After Ed’s death, you had the sensation that he was still present, listening to you. You write, “I would like to protect him, perhaps from myself; I would like to protect his consciousness.” What does protection mean there?

RG The desire to protect Ed is so embedded in our relationship and in my psyche that it morphs into the notion that he is still with me in some fashion. Later, when I start talking about him in the past, I say the past tense drives nails through him. I can’t protect him from becoming a memory, or a story. As for protecting him from myself, I do mean from my version of his life, this very book, a story distorted by my point of view and my desires, including the need to protect him from the violence of language itself.

In general, I think nurturing and consuming are two aspects of love. Perhaps they are opposites. With a baby or a toddler, and sometimes with a lover, we turn it into play, like saying that we want to “gobble him up.” Ed inspired a high degree of nurturing. He was often sick, for example; it was normal for him. Like other mighty sexual beings, he offered me and others access to his amazing beauty that by its very nature should have been beyond our reach—he gave us an invitation to consume.

SE One dream Ed recounts in that final section of the book goes “Before that the cosmos begins. I’m a voluptuous angel in a black bikini. I drape a diamond shawl over my shoulders and dance midair for the others, spreading my legs, curling like an embryo, a pose for every aspect of life.” I drew a little heart next to that one—it’s hard not to fall in love with Ed. Do your readers encounter Ed? Can a book facilitate an encounter with someone who has died?

RG I suppose the answer is a resounding yes and a resounding no, depending on what you mean by “encounter.” I like to think that the reader absorbs Ed, that Ed somehow lives inside the reader as a person from the same world as the reader. The weight of Ed’s psychic life, conveyed through his actual dreams, is transferred to the reader. Maybe that is a kind of love. We offer our friends and lovers our psychic stage to act out their dramas, their lives. How do their deaths affect this relationship? To install Ed inside the reader may be impossible, but most goals in writing are impossible, like absolute clarity, or turning words into objects, or creating enchantments that directly change the world, as Rimbaud intended.

SE You dedicate the first section of About Ed, “Everyman,” to George Stambolian—a writer, an editor, and a professor of French. His work appeared regularly in gay publications like Christopher Street and the New York Native. I know he published a story of yours in his first anthology, Men on Men: Best New Gay Fiction. Who was he to you? Why dedicate “Everyman” to him?

RG George Stambolian was both exotic and immediately recognizable to me. He was a New York A-gay, handsome, cultivated, stylish, with a fabulous beach house in Amagansett. He was Armenian. Perhaps Jews and Armenians share some affect—because of the genocides? He was like one of my great aunts—fretful, loving, aggressive, a bit of a noodge. And he was the first editor who published my writing and the writing of my little West Coast New Narrative group in a book from a trade press. The trade presses were indifferent to us, which is to say the gay mainstream, where the ideal novel was written with a Violet Quill. Our influences were more continental—more French. George was a French scholar, as you say. I think that’s why he was not put off by our experiments.

He was dying in 1991 as he finished editing Men on Men 4: Best New Gay Fiction, and I am such a painfully slow writer that I transgressed his increasingly urgent deadlines. I was working on the long story “Everyman,” which eventually became the first section of About Ed. George would call me up and say, “Bob, I’m dying, give me the story now.” I’m afraid I caused him some distress. He was gone by the time the book went to press, so I dedicated “Everyman” to him, part thank-you, part apology.

SE In About Ed, you say that it might take a generation to “reacquaint ourselves with the dead.” A number of literary presses are publishing and republishing the work of writers like Steve Abbott, Essex Hemphill, Bo Huston, Lou Sullivan, and others who lived and died with AIDS—big presses and small presses, older and newer. Are there others you hope will receive their flowers? And are there particular complexities that new generations should consider as we acquaint ourselves with them?

RG I’m glad you mentioned Bo Huston, whose work should be well known. We could add Sam D’Allesandro, a heart-stopper, and Lawrence Braithwaite, a wildman-seer (read his cult novel Wigger) from my neighborhood of the writing world, and Bob Flanagan too, though he died of cystic fibrosis. Richard Ronan is another, not a literary neighbor but a lovely poet and playwright, Zen and Catholic. I fear he has totally disappeared.

As for complexities, the seventies and early eighties are often disparaged as a time of mindless excess, and it certainly was. But everyone arrived at his sexual Eden with his particular problems. This period was also very engaged. It is amazing how much was accomplished in all departments. There were communes experimenting with new social relations. There were radical politics and mainstream politics and a new voting bloc—by “voting bloc,” I mean visible power. Queer politics did not begin with ACT UP [the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power]. There was the construction of a readership through gay presses and journals. All of this was achieved in the maw of a society that criminalized and pathologized us.

SE Did this engagement across the queer politics and publishing of the time have a particular quality or signature? And where do you see sexual Edens now, if at all?

RG Oh, sexually, I think we were frantic. We were making up for the gender socialization we missed in high school and college. Just being part of a gaggle of gays sitting on a stoop was amazing.

As for the present, generally, I flee from questions designed to make me relevant. I don’t think it’s a good look for a seventy-eight-year-old. But your question interested me enough to survey some friends: Nayland Blake, Matt Sussman, Noah Ross, and Eric Sneathen. Noah says maybe in our dreams, maybe at certain gyms, and maybe when the fourth dimension pierces our reality. Of course, the internet shapes sex in our era (identifying pollinators for rare blossoms like me), and Eric says it has made our sexual categories more porous. Isn’t that interesting? In the first place, the opposite was true—our sexual categories had to be resoundingly recognizable online. Nayland describes being the facilitator of a queer orgy at a Kink gathering’s private campground, “a free-floating community that gathers at intervals to fuck and enjoy each other.” And Matt describes Honcho, “a five-day queer dance music campout in the woods. Its vibe mines a nostalgia for the gay seventies. The organizers and attendees put so much care into creating a space where the stakes of such an experiment become clear: camp is a staging area to try out how we, as queers, want to show up for each other in the world and to experience what gets created when we do.” So, this is Bob’s communal answer.