To read more of The Yale Review’s folio “Is This Real?,” click here.

Paul

Is the self real?

Sheila Heti

Now shelly was realizing that the imperfect premise was this: that she was one person. It actually made much more sense to conceive of her flesh containing somewhat different people, each with their own history, made from the facts of her life; each with their own slightly or vastly divergent goals, fears, pleasures, and complexes. For instance, one person inside her was always afraid of what other people might think, and believed that if someone was mad at them, they would die. This person’s primary motive was to appease. But there was someone else within her whose primary motive was to get away from everyone, for only in solitude could they think, and they cared not at all about the opinions of others. Then there was someone who believed that making a romantic relationship work was the best thing a human could accomplish in this lifetime, and that solitude was an escape. One self clung to frugality, another loved indulgence. Each of these different selves was robust, complex, and could not be satisfied by the satisfactions of the other ones—each self always holding out for their most desired end, unhappy until it was fulfilled—making total happiness for Shelly impossible.

Shelly, as a result, never really knew what her goals were. And she never felt like she had made the right decision, for certain selves within her always felt left out. How, then, to live or make decisions? Which self did she respect the most, which one did she trust? Which inner self, if she tried to follow their wishes and demands, would bring her closer to happiness, and which, if she gave in to their wishes and demands, would draw her closer to despair?

So Shelly began to keep a journal. In every moment of indecision or doubt, she would try to name the selves that were competing within her. One time it was the red wizard, who feared the influence of other people. Another time it was the wiggly blue line, who was terrified unless an outside authority told them they were good. Shelly started drawing maps, charts, diagrams, trying to understand what terrified each part, and what brought each part peace. Which of these selves did she value too much? Which were undervalued? The more she thought, the more she saw that she had never been one Shelly, as she had believed. She had always been a quorum. The first year that she began taking notes, it seemed to be a quorum of five. Within two years, however, the subtler members of her being began to make themselves known. The most interesting discovery she made she named Paul.

Support Our Writers

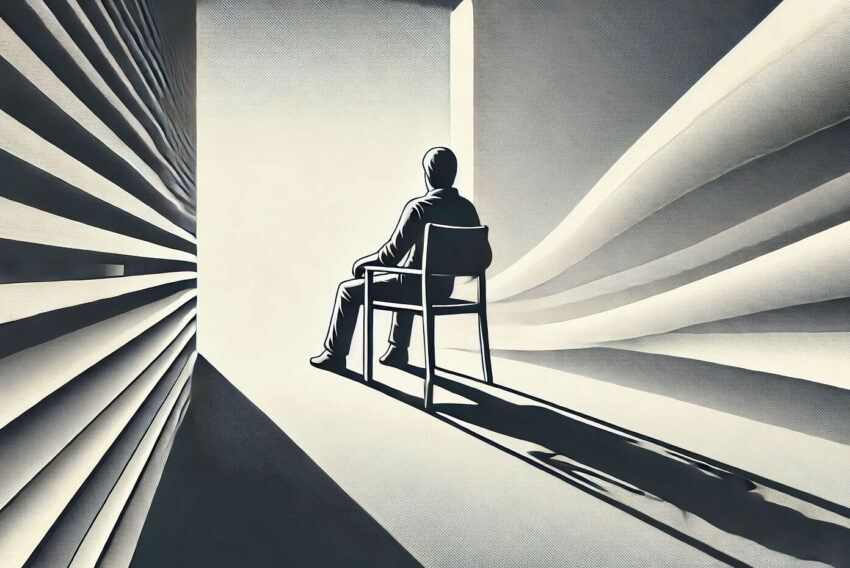

Paul had a very minor request, no matter what the situation: he wanted to sit down. If Shelly was sitting down, Paul was okay. Somehow sitting down was all that was required for his peace: sitting, he felt sure that the world would sort itself out. Everything could be falling down around Shelly, the walls could be caving in, but if there was a couch or a stool to sit on, Paul felt everything would be okay, or at least not as bad as things could possibly be.

And so Shelly began sitting as often as she could. Of course, she had read the reports: it was bad to sit—bad for the heart, the core, overall health. Everyone around her was buying standing or walking desks. People were walking and standing. She would see grown adults taking every opportunity to stand on the bus, appreciating its jerks, which tested and strengthened their balance. Shelly, sitting, watched them wobble.

This was the beginning of her very best years. How small a thing—this tiny adjustment! And how she never would have discovered it if she had not realized that she was made up of separate, complete, and inassimilable parts. Paul’s demand was so minor, so humble, and so sincere. It filled her with love and sympathy. She imagined the face of this inner part as being very mild, with smallish features and a moon face. Something about Paul made her feel content and sleepy. She was realizing that if she could only appease Paul, the other selves quieted down. It was as if his minorness was not actually minor but the entire base of who she was. It was as if all the selves inside her had been born from Paul, so that at root she was a person who wanted to sit.

Years of therapy had not brought her anywhere near to this solution; in fact, therapy had only made her ever more despairing of her bottomless complexity, which she felt she would never untangle or cure. But the more she sat, the more it dawned on her that she could stop seeing her psychiatrist. So she did. She didn’t worry about her circulation, her cellulite, her flattening ass. She reminded herself, After all, this is what Paul wants, and all the other parts of her nodded: Paul should be pleased. Each of them still had their own wants and needs, but these wants and needs felt less urgent now. How simple she was, at heart! But she had only come to this surprising knowledge by first accepting how multiple she was, turning away from her presumption of a unified self.

When her friends remarked on her new peace, asking if it came from meditation or perhaps from exercise or maybe prescription drugs, she didn’t tell them about Paul, or about sitting more. After all, she knew that not everyone had a Paul inside them. This was only her private solution, and she didn’t believe that telling them would help. Who among them would go through the tiresome mapping she had gone through, dividing up wants and fears into separate selves, then ultimately finding the quietest personality of all, and honoring it always. It was not the sort of advice that could be passed on over drinks. One day she thought that maybe she should write a book about it, to explain it all: a textbook or a memoir. But then, she realized, she’d have to go around the world, get on planes and off them, and climb narrow stairs onto stages. All this moving about would mean less sitting for Paul, and she would go back to being as anxious and unsatisfied as she had been when she first started her speculations. No. She would not write a book. She would continue to honor Paul.

Shelly’s home had a chair in every room. Although the pleasure this gave her was small, she didn’t seek a higher one. She had found the smallest pleasure of all, and this proved to be enough.