when i was a kid, a painting hung in our living room. Alluring and moody, it loosely depicts a street of receding row houses, the sky and buildings in choppy shades of blue and a few errant red and yellow streaks, all dashed by sharp, thin black lines representing the bare limbs of trees. I knew that it had been painted years earlier by a friend of my dad’s, a then sixteen-year-old named David Lynch. I also knew that Lynch had later become famous. For a while, before I’d seen any of his films, the painting, along with my dad’s stories, formed a portrait of David Lynch in my mind. He was a kind of friendly specter over my childhood, peering out from the world he’d painted an eerie and enveloping blue.

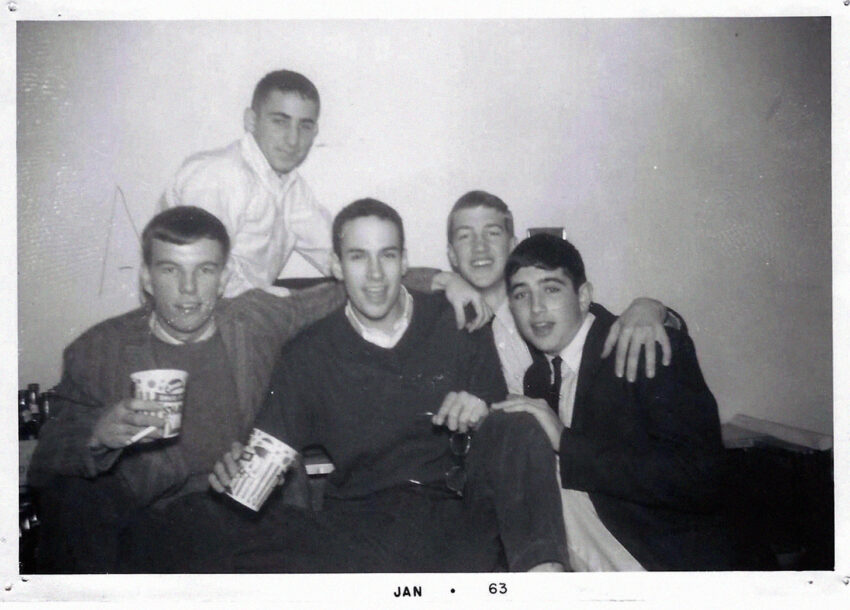

My father, Bill Frazier, met David in Alexandria, Virginia, in the early 1960s. David had just moved there from Idaho. He and my dad both attended Francis C. Hammond High School and became friends when they joined the same fraternity. (Those were the days when high schools had fraternities.) They were friends with another fraternity brother, Toby Keeler, whose father, Bushnell Keeler, was a pivotal figure in Lynch’s early life as an artist. My dad and David fell out of touch after college.

The day after Lynch died, I called my father and asked him to tell me some stories of the time they spent together, when Lynch was being formed as an artist and a person.

—will frazier

He was always sketching. One morning, during homeroom, I said, “David, sketch me something.” He drew a little row house. His notebooks were covered in sketches.

There were four or five fraternities and a similar number of sororities. There was the jock crowd versus the social, fraternity crowd. Ivy. Everybody was Ivy. “Oh, he’s so Ivy.” “Oh, she dresses so Ivy.” In a note in an old yearbook, David wrote, “Woweeee William you are a very Ivy friend.”

There was a one-story frame shack called the Cameron Club off Duke Street. We had fraternity parties there. Some kind of rock-and-roll band would play. One older guy had to be the chaperone. We danced and drank beer and went nuts.

We were sixteen and seventeen. We would hang out all weekend. Sometimes we’d drive to Georgetown, across the river in D.C., and smoke pipes and drink tea from Russian tea glasses with a little dish of cherry preserves on the side. We smoked pipes before we smoked cigarettes. We would sit there and drink and smoke and pretend we were intellectuals.

We wore ties. With our button-down Gant shirts, we wore ties that we bought at the Georgetown University Shop. All the fraternity guys bought their ties there. That was the unofficial uniform for our public high school. It was kind of unusual. Ties and Gant shirts and khaki pants with Weejuns loafers. But David wore these gross white tennis shoes that looked like they were about twenty years old. He wore those every day with his shirt and tie. Grubby tennies, we called them.

We took our dates to the drive-in together. We would pull up to the exit and whichever one of us wasn’t driving would hop out and unhook the chain so we could sneak in through the back. We brought a case of beer in the trunk. I remember seeing Days of Wine and Roses with David. It was about alcoholics, actually. It was a fun movie. Or it wasn’t funny; it was a tragic movie, but anyway . . .

One night we were in some bar—a country music bar down on M Street—and we had only one or two fake IDs. We didn’t have enough for everyone. After the waitress looked at an ID, we’d pass it under the table to someone else. “Oh, okay,” she said.

Behind City Hall in Old Town, in a decrepit three- or four-story row house, David rented the top floor for something like forty dollars a month. It was his painting studio. I’d bring over a six-pack, stepping carefully over people sleeping on the steps. Next door was a women’s shop that sold scarves. Frankie Welch, I think, was the owner’s name. David painted her a sign that hung over the door.

David befriended two guys who opened a shop on the lower end of King Street, which, back then, was pretty much warehouses that were still being used as warehouses. It was not restaurants and shops like it is now. They lived in a big house. They were restoring it. I remember carrying up, with David, these octagonal bricks that were in the floor of the basement. David spent a lot of time working for them, making a bit of money, which probably helped him pay for his studio. We’d buy little green bottles of beer from a place down there. The guy didn’t care who he sold to.

We drove to University of Maryland to see Peter, Paul and Mary. We both had dates and nosebleed seats. It was a big deal for us—this would’ve been ’62 or ’63—to see them. This was before the Beatles were really big. It was probably the first concert I ever went to.

At the end of the school year, we drove to Virginia Beach. Whoever was dumb enough to rent to teenage fraternity boys would rent us some broken-down shack or a room at some broken-down motel, and we’d crash there for the week.

Our friend Toby’s father was a full-time artist. I have a pen-and-ink drawing of a sailboat that he did. He went to Nantucket every summer. He would rent a little studio on one of the docks and sell his art there. He befriended David and became his mentor. He and Toby’s mother divorced, and he went to live on his sailboat over in Maryland somewhere. It was called Up Your Anchor.