For there she was.

And here she is.

Virginia Woolf is in Charleston & in Richmond & at Monk’s House in Rodmell & at Garsington & in Gordon Square. She is, on August 2, 1920, in “the middle of baking a cake, & fl[ies] to this page for refuge, to fill in moments of baking & putting in my bread. Poor wretched book! Thats the way I treat you!—Thats the drudge you are!”

She finds she cannot write. “I held my pen this morning for two hours & scarcely made a mark. The marks I did make were mere marks, not rushing into life & heat as they do on good days.”

And she cannot settle. “I raise my head from making a patchwork quilt.…Sat for an hour, scratching out, putting in, scratching out.”

“Oh the servants! Oh reviewing! oh the weather!” she despairs. “Compliments, clothes, building, photography—it is for these reasons that I cannot write Mrs Dalloway.”

There is, she writes, “nothing to record.”

But then there is a shift, and the “nothing” becomes something, and the something becomes writing: “The sun streams (no: never streams floods rather) down upon all the yellow fields & the long low barns; & what wouldn’t I give to be coming through Firle woods, dusty & hot, with my nose turned home, every muscle tired, & the brain laid up in sweet lavender, so sane & cool, & ripe for the morrows task.”

“I can write & write & write now: the happiest feeling in the world,” she notes on December 13, 1924. Write & write & write: three words, two ampersands. She loves the ampersand, loves its uprightness, its concision, its self-confidence. It is the connective tissue of her diaries. Her ampersands are one & one after another flourish. Up and around the pen goes. And onward.

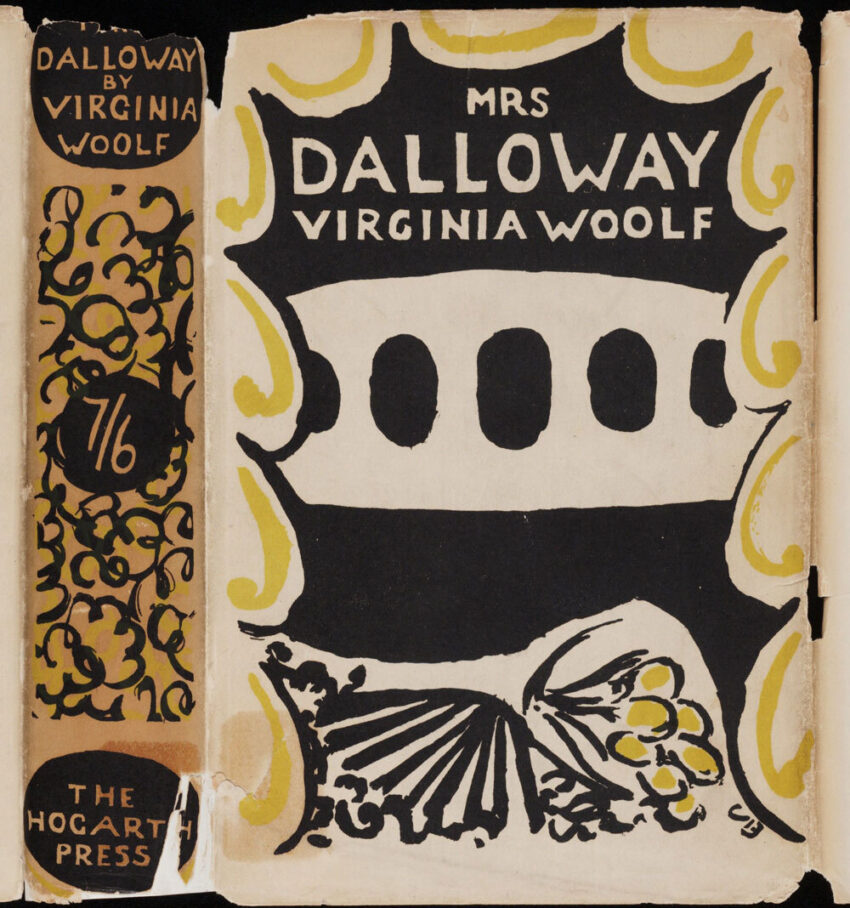

published by leonard & virginia woolf at the hogarth press, 52 tavistock square, london, w.c., 1925, says the title page of the first edition of Mrs. Dalloway, the ampersand joining the publishers, the typesetters, their marriage. Vanessa Bell designs the cover in yellow and black, and it looks a little like curtains, possibly a bridge reflecting in water, definitely foliage. The price—seven shillings and sixpence, a 7/6 on the spine—is held in a tangle of vines that looks like a nest of &&&.

& is her glyph, her imperative, one thought reaching over to the next.

And though an ampersand marks the colophon, leonard & virginia woolf, there are none in the text itself. The accretion of the “and,” the &, its velocity punctuating and animating her diaries, is invisible in the book. One thing, one impression, slips into another, separated only by the comma. The “and” becomes an inward breath, an inhalation, tacit.

It is Clarissa mending her green dress for the party that evening: “Her needle, drawing the silk smoothly to its gentle pause, collected the green folds together and attached them, very lightly, to the belt. So on a summer’s day waves collect, overbalance, and fall; collect and fall; and the whole world seems to be saying ‘that is all’ more and more ponderously, until even the heart in the body which lies in the sun on the beach says too, That is all.”

Collecting and falling: the imperceptible moment of the turn of the needle, the turn of the breath, the space, the gentle pause, the overbalancing of the world.

And the pause is the stutter of Clarissa’s heart, “affected, they said, by influenza,” a misfiring of the heart in the body which lies in the sun on a beach, known and felt. And the duration of this caesura, where one thing becomes another, is different for Clarissa, for Peter, for Sally, for Richard, for Rezia, who cares for Septimus, the shell-shocked soldier back from the trenches. For each of them, Woolf slows the becoming, slows the understanding, the possession of each moment as it overbalances into the next.

Words are vapor trails above St. James’s Park: “A C was it? an E, then an L?…in a fresh space of sky…a K, an E, a Y perhaps?” Words are ephemeral: memories & breaths & desires, “languishing and melting in the sky.” They are threads of sound, “a voice bubbling up without direction, vigour, beginning or end.”

And words are concrete marks too. They are things, metal type to be set in a compositor’s stick at the Hogarth Press, inscriptions to be traced with a finger.

Rezia brings Septimus “his papers, the things he had written, things she had written for him. She tumbled them out on to the sofa.…Diagrams, designs, little men and women brandishing sticks for arms, with wings—were they?—on their backs; circles traced round shillings and sixpences—the suns and stars…the map of the world.”

The map of the world of Mrs. Dalloway slips and tumbles.

This slipperiness can be beautiful, the hum of the household as symphony: “Faint sounds rose in spirals up the well of the stairs; the swish of a mop; tapping; knocking; a loudness when the front door opened; a voice repeating a message in the basement; the chink of silver on a tray; clean silver for the party.”

And it can be disassociated, dissonant, the sound of the car backfiring on Bond Street, the words falling out of the sky. It can be Septimus trapped in the ampersand, in the repetitions of trauma, the iterative return to pain.

It can be the world too full of things, “this wreckage” in the antique shops on the corner of Conduit Street, Miss Kilman trapped in the Army and Navy Stores with “all the commodities of the world, perishable and permanent, hams, drugs, flowers, stationery, variously smelling, now sweet, now sour.” One comma after another, the breaths shorter and shorter.

So how can she finish writing this book?

“It is a disgrace that I write nothing, or if I write, write sloppily, using nothing but present participles. I find them very useful in my last lap of Mrs D,” Woolf notes on September 7, 1924. “Suppose one can keep the quality of a sketch in a finished & composed work? That is my endeavour.”

And she does it.

“It is disgraceful,” she writes six weeks later, on October 17. “I did run up stairs thinking I’d make time to enter that astounding fact—the last words of the last page of Mrs Dalloway; but was interrupted.…‘For there she was.’ & I felt glad to be quit of it.”

Interruptions and ampersands and commas, the stuttering of the heart, nothing but present participles. She runs up the stairs, making time to enter the astounding fact, and we all converge in that lighted room, the windows open to the evening air.

And we are held within the breathturn of the book. It becomes Mrs. Dalloway.

“I meant to write about death, only life came breaking in as usual,” Woolf writes in February 1922. “I have taken it into my head that I shan’t live till 70.…I was feeling sleepy, indifferent, & calm; & so thought it didn’t much matter, except for L. Then, some bird or light I daresay, or waking wider, set me off wishing to live on my own—wishing chiefly to walk along the river & look at things.”

Life is too full of &s, too propulsive, too full of desire, of wishing, walking, looking, writing.

“I like to go out of the room talking,” she says, “with an unfinished casual sentence on my lips.”

For there she was.

This piece was first given as a talk at the 2025 Charleston Festival in Sussex, England.

Newsletter

Sign up for The Yale Review newsletter to receive our latest articles in your inbox, as well as treasures from the archives, news, events, and more.