To read more of The Yale Review’s folio “Is This Real?,” click here.

Michael Crichton

Is celebrity real?

Joanna Radin

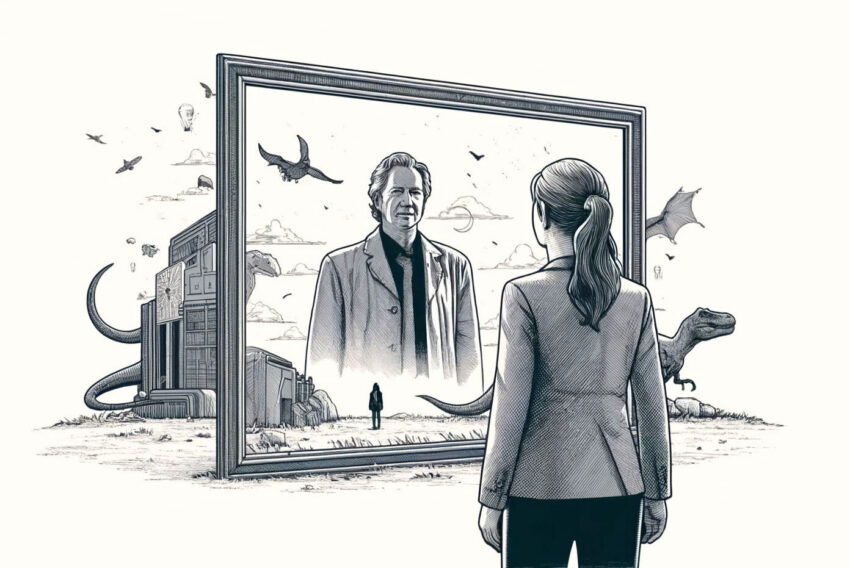

I have spent the better part of the last decade channeling Michael Crichton. Born the same year as the Manhattan Project, he grew up, a generation before I did, in the suburbs of New York City. He spun his Harvard degrees in anthropology and medicine into a career as a blockbuster novelist and filmmaker. He was as much a pop artist as his friend Jasper Johns; he networked his way into becoming a magus of an entire culture industry and, finally, a household name, synonymous with the ambivalent emotions of wonder and fear conjured by late twentieth-century science. He aspired to create myths about the life-changing geist of his own zeit that could travel via as many mediums as possible. Books, TV, film, design, computers. Maybe even me.

I am often asked when I got into Crichton. My answer has become a different question: When did he get into me? The height of his fame in the mid-1990s—when he published Jurassic Park, his postmodern Promethean tale of de-extincted dinosaurs, and created the realist medical drama ER—coincided with my own coming of age as a prototypical girl in STEM. My schoolteacher parents were pleased to see their eldest daughter experimenting with social mobility via science at a time when its stock was riding high. I entered science fairs. I went to science camps. I read Michael Crichton, whose books about the Pandora’s box opened by biomedicine sat on my father’s shelves. A Case of Need, published under a pseudonym five years before Roe v. Wade, lays out a scientific argument for a male doctor’s right to perform an abortion (in contrast to a woman’s right to receive one). The novel ends with seven fourth-wall-breaking appendices, highlighting new moral problems brought on by biomedical innovation, including euthanasia and the definition of death. The Andromeda Strain (1969) warns against allowing a secret cabal of scientific men to make decisions about germ warfare. And, of course, Jurassic Park screams that just because scientists can manipulate life doesn’t mean they should.

Crichton’s novels of fictionalized fact had a distinctive effect on me, conjuring desires I could not yet name. I recognize them now as the stirrings of an interest in power and the men who seem to wield it, albeit imperfectly. Would becoming a STEM girl lead me to such men? Could I become one? Should I? Yet what Crichton had to say about science suggested that it was becoming too important to be left to the scientists. This made his ideas both alluring and suspect—a crack in the compulsory reality of my suburban life and public school.

It was only after Crichton died in 2008 that I started to take stock of how much of my life had been shaped by his ambition. While pursuing a graduate degree in the history and sociology of science, I reread all his novels, startled to find that he had already metabolized the ideas of my professors: The words of one, a feminist who observed that innovation in household technology had ironically created more work for mothers, were soliloquized by the sexy, black-leather-clad chaos theoretician in Jurassic Park. Sometimes these professors were even named in the bibliographies Crichton used to demonstrate his credibility, as in his last book, Next (2006), where my own Ph.D. adviser’s adviser was cited for exposing the lack of regulation in the medical market for human remains. Weirder still, the Harvard scientists at the center of my dissertation had been his professors, initiating him into a world that I had decided (or had I?) to make a career of historicizing. This intergenerational ouroboros of influence reactivated my girlhood fascination with his fiction. Now I was no longer a girl. And I had not grown up to be a man. I was a woman struggling to make sense of just how much Crichton had doctored my imagination.

The currents of Crichton's fantasies have illuminated and redefined my own relationship to reality.

My reintroduction to Crichton gradually bloomed into obsession. I talked to people who had known and worked with him, watched recordings of his interviews, even located his childhood home on the same coast of Long Island where I was raised. As I consumed ever more of his content, I started to feel that we were kindred. We were both professionally preoccupied by manipulations of life in an age of mass culture, even if our politics often clashed. I caught myself raving about Michael as though he were a friend who had never been able to speak for himself. I worried that I sounded delusional, but I was even more troubled by my uncontrollable desire to be in conversation with him and thus amplify his reputation.

I became mystical. I attempted to commune with him, emboldened by the knowledge that, in life, he had practiced techniques of parapsychology and divination. In his 1988 memoir, Travels, he questioned scientific skepticism about these experiences. The most intense period of his exploration of these skills—which involved reading auras, using tarot cards and the I Ching, and attempting to locate sunken ships via remote viewing—suggested to me that they had contributed to his ascension from merely famous to iconic. I felt he wanted me to know that achieving this level of influence had been intentional. And that it had also caused him great pain. And that this had something important to teach me.

the year i was bat-mitzvahed, Crichton was invited to address the National Press Club, a talk broadcast via C-SPAN. Nearly thirty years later, I watched the digitized footage rapt and in search of clues that would explain his hold on me. At fifty, he appeared fresh-faced, his thick, dark hair showing no silver. Smart glasses, dark suit, white oxford shirt, maroon tie—a uniform he’d maintained since his Ivy League days. He adjusted the microphone to accommodate his six-foot-nine frame. Here was a powerful man.

Despite the omnipresence of his ideas, people weren’t hearing him the way he wanted to be heard. He resented being criticized for his portrayal of women and minorities. He was wary of a coming world in which men like him did not set the terms of reality. He blamed the shoddy standards and polarizing tendencies of the American mass media.

Crichton couldn’t entirely exculpate himself, saying that an increasingly dismal view of journalists had affected his own ability to “do the job” when researching his books. Peers like Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion, and Tom Wolfe had borrowed from fiction in the service of their journalism. Crichton too deployed his facts with the goal of expressing cultural truths that transcended genre.

He described his ideal relationship to information as trying to find out the “current fantasy,” a phrase borrowed from Merry Prankster Ken Kesey. The current fantasy, Crichton explained, is a vibe or coming wave being “bruited about.” (CSPAN’s auto-closed captioning transcribed “bruited” as “brooded,” which suggests an incubation.) Under the right conditions, and with sufficient publicity, a charismatic artist might transmute a current fantasy into a new reality, reconciling past and future, and hatching new forms of life. Like a STEM girl. Or de-extincted dinosaurs—unlike the CGI-depicted monsters in Spielberg’s fantasy, a thing with feathers.

Crichton shared a specific current fantasy with the National Press Club. It was of a new and improved form of accessing information: the internet. An early adopter of personal computing, he depicted this emerging, electrified web as a more ideal medium than the ones he had already massaged. Editors at the magazine Wired reprinted the talk and gave it a new title: “Mediasaurus.” The subhead read: “Today’s mass media is tomorrow’s fossil fuel. Michael Crichton is mad as hell, and he’s not going to take it anymore.”

The first time I typed the word mediasaurus, my computer generated a startling autocorrection: medias auras. The ghost in the machinery of the culture industry, a force hard to discern in the jargon of science, seemed to reveal itself in this phrase. The artificial intelligence in my word-processing software named the possibility that books, films, and all kinds of technology generate ambient sensations and have far-reaching but obscure effects. Like the ones that have led me to feel that Michael is somehow inextricable from who I have become. Crichton was a prolific artist who also made himself into a kind of infrastructure, or even an atmosphere. Like microplastics, or trace antidepressants in the drinking water, Crichton is a cultural forever chemical that has fundamentally changed the conditions of existence. The currents of his fantasies have illuminated and redefined my own relationship to reality. Media’s auras enable me to speak with Crichton as well as to speak through him. To paraphrase one of my teachers, you never know which gestations will save the world.