To read more of The Yale Review’s folio “Is This Real?,” click here.

Storytelling

Is narrative real?

Mona Oraby

I.

Two scholars were invited to deliver keynote addresses at the conference on desire and intimacy in the study of religion. The ethnographer was familiar with the work of the other scholar, an anthropologist, but they’d never corresponded and were meeting each other here for the first time.

The anthropologist’s raised hand was the second one the ethnographer called on during the question-and-answer period following her talk, “Reality Problems: Desire in Ontological Multiplicity.” He offered a comment and a question.

You’ve shared something tender and incisive, he said, allowing us to wander through the narrative landscapes of love and violence, memory and destruction, motherhood and loss. In storytelling, Susan Sontag says we come to know truth as well as fiction.

Then he asked her to articulate how this work contributed to her field.

Not long after, they walked side by side toward downtown Evanston, where they were expected for predinner conversation with the graduate student presenters. One of these students, a scholar of American religion who used the methods of literary criticism, walked alongside them. Earlier, the student had asked the ethnographer to clarify what she meant by “staying on the same plane” as our objects of study, a phrase she had borrowed from Rita Felski, as a methodological alternative to fieldwork, which Matthew Engelke has described as “the central rite of passage for the anthropologist.” How can we do that? the student had asked. How do you do that? By maintaining fidelity to the subject’s ontology, the ethnographer had replied. I do not know her life better than her experience of it.

Your project is a companionship between anthropology and literature, the anthropologist said to the ethnographer as they neared their destination. You don’t use anthropology to explain literature. They are companions.

She jotted down the note on her phone as he spoke.

The next morning, he sat next to her before the first session commenced. From a large tote bag printed with bulbous fluorescent flowers, he pulled out a deep-red yet muted block-print fabric.

I have a gift for you, he said, extending the folded textile toward her. It’s a scarf from Sindh.

She laid her hands on the repeating floral medallions. A flower from a garden, she thought, wordless.

II.

elishva is believed by some locals to hold special powers of baraka, the ability to forestall or avoid catastrophic events—so long as she is among them when these events occur. One Sunday, minutes after Elishva boarded a bus headed to the Church of Saint Odisho, a massive explosion went off mere yards away. All the passengers were spared the explosion’s deadly effects. Elishva, who appears to be deaf and blind, did not notice. Other residents of the Bataween neighborhood of Baghdad, citing her blank looks, think she’s just a senile old woman. As far as they know, she lives alone in a too-large house, beautiful and dilapidated, filled with antique wares that she refuses to sell.

It’s not exactly true that Elishva lives alone. Her cat, Nabu, and the specter of her son, Daniel, and Saint George the Martyr, her patron saint, fill Elishva’s life with abundant presence.

Elishva loves Saint George. He holds a central place in her life, which is her home. In the parlor, a large picture of him hangs, framed in heavy carved wood, between smaller pictures of Daniel and her late husband, both now gray. Elishva sits in her usual spot on the sofa facing Saint George. She speaks with him nightly, when the stillness of the icon transforms into a portal between his world and hers, and through him Elishva hears the Lord.

In these early years of the U.S. occupation, Elishva pleads with her favorite saint.

She is among the thousands of mothers whose sons went missing or were forcibly disappeared between the years 1980 and 1988 during the Iran-Iraq War. And like some of them, she expects Daniel to come back one day, any day now. Still, over time, the number of people willing to listen to her talk about her son dwindled. Even the women at church forgot what Daniel looked like; they accepted that he had perished long ago. But Elishva remains convinced that Daniel is alive. It makes no difference that a grave with his name on it stands over an empty coffin in the Assyrian Church of the East.

In these early years of the U.S. occupation, Elishva pleads with her favorite saint. She begs Saint George to reveal Daniel’s whereabouts. She weeps. They argue. She extracts from him the promise to reveal whether Daniel is dead or alive, where his remains are, or when he will return. Even so, he admonishes her. “You’re too impatient, Elishva,” he says one night. “I told you the Lord will bring you peace of mind or put an end to your torment, or you will hear news that will bring you joy. But no one can make the Lord act at a certain time.”

Elishva tolerates Saint George’s scolding. She ignores the long lance he holds in his right hand, pointed at a dreadful dragon he hasn’t yet killed, and the elaborate armor covering the length of his body. Instead, through thick glasses, she focuses her eyes on his delicate face.

III.

operation desert shield was the name President George H. W. Bush gave to the U.S.-led coalition defense of Saudi Arabia soon after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. The subsequent air and ground offensive to rid Kuwait of Iraqi occupiers was known as Operation Desert Storm.

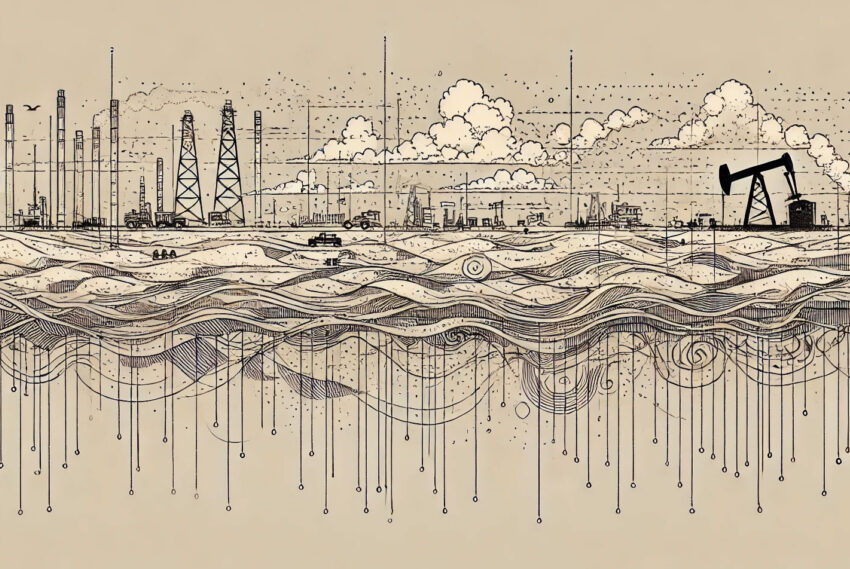

Saddam Hussein refused to let anyone else benefit from Kuwait’s riches. He sent men to blow up Kuwaiti oil wells, pipelines, and pumping stations as the Gulf War neared its end. When Iraq’s military at last fled Kuwait on February 26, 1991, over six hundred oil wells had been set ablaze.

Black rain fell to the earth, staining cars and concrete and skin.

The wellhead fires—“towering infernos”—burned for close to a year. Crude oil spewed across low-lying areas and trenches in the desert. The firefighters stationed in the oil fields came to call their task Operation Desert Hell.

That spring was unusually cool. Respiratory diseases began to develop among children and the elderly. The smoke was so thick that it blotted out the sun; drivers turned their headlights on in the middle of the day. Black rain fell to the earth, staining cars and concrete and skin. The inky rain was recorded as far away as southern Turkey, over six hundred miles from Kuwait City, and in the Himalayas, farther still. Smoke-contaminated clouds marred near and distant skies.

Roughly one and a half billion barrels of oil escaped into the environment. Most of that oil burned, but eleven million barrels spilled into the Persian Gulf. When the firefighters put out the last fire in November 1991, about three hundred oil lakes remained spread out across the desert. Airborne soot and oil had fallen from the sky and mixed with sand and gravel to form what’s called “tarcrete.” This, the largest soil remediation project in the world, has been stalled for decades.

IV.

on june 30, 2022, the International Committee of the Red Cross supervised a handover of human remains. The remains of nine Iraqi soldiers and thirty-six Iranian soldiers were repatriated.

V.

the ethnographer sat across from her brother on the upper deck of the local crab house. Their server told them that soon the Baltimore fisheries, rather than close between November and May, would import blue crabs from New Orleans, where the Gulf of Mexico stayed warm through winter as the Chesapeake’s waters cooled.

Her flight to Chicago departed in two days. As they ate, she explained that she was still unsure about the keynote address she’d deliver at her alma mater. Maybe she was trying to hold too much at once. She wanted her talk to draw from a chapter on war in the book she was writing, which made a case for literary worlds as proper objects and literary figures as proper subjects for anthropological reflection. She also wanted to incorporate thoughts from her Yale Review piece, which played with some ideas from that project.

What do you think? she asked. Wiped clean by paper napkins dunked in water, her right hand held a clear plastic cup by the rim, and she nursed what was left of her beer.

So the audience won’t know which part is fiction till the end? Yoooo! His eyes, wide and expressive, looked from her to the claw he had just cracked, delight gathering at the corners of his mouth. He liked to save the claws for last. The sun had set over the harbor, and the neon Domino Sugars sign glowed warm in the distance against a darkened sky.

That’s the thing, she said. Anything I try to say about these wars is a kind of story. I didn’t witness the U.S. occupation of Baghdad, but I know that political violence has been normalized in Iraq for decades. And the dead are still being found. We were in Riyadh during the First Gulf War, but even there we were so young. My main memory is of being evacuated by the Americans.

Right, to France. I remember the soldiers.

It was either Spain or Germany, she corrected him. I think they fed us bologna sandwiches in a military hangar.

He thought about this. Mom would know, he said.

She nodded, saying nothing, recalling their argument back in June. She would not break the monthslong silence, again, to resolve the doubt. In a repetitive motion, he moved white meat from his salt-caked fingers to his lips until only spent carcasses lay between them.

Note: The account of Elishva and her world as well as all quotations in part two are drawn from Ahmed Saadawi’s novel Frankenstein in Baghdad, translated from Arabic by Jonathan Wright.