In Objects of Desire, a writer meditates on an everyday item that haunts them.

My Face

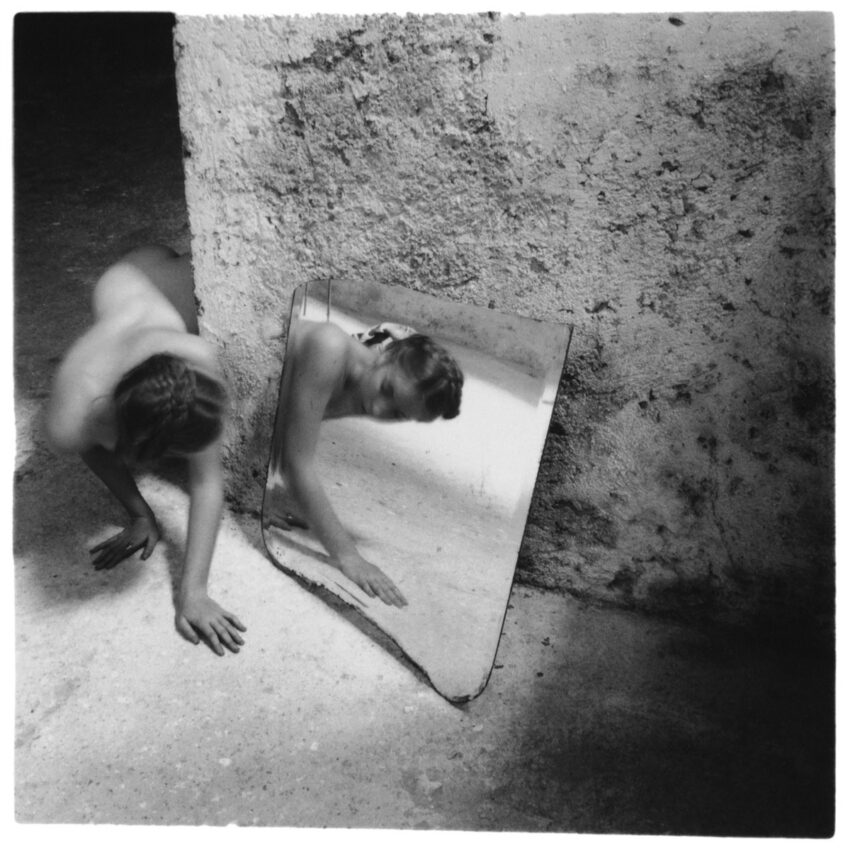

When I look in the bathroom mirror, I see my past and future selves

Melissa Febos

I locked the bathroom door and stared in the mirror at my face: tan and green-eyed, freckled by dried toothpaste spatter. No matter how long I looked, I could not remember that face after I turned away. I grasped at its slippery yolk, trying and failing to conjure my own image from memory. It was a cognitive riddle that I dared not speak, a quirk of brain. I was young then, only eight or eleven or sixteen.

The inability to see images in one’s mind is called aphantasia, but I could see everything in my mind except my face. A separate task was trying to see the good there. As a child, I shuttled my gaze from mouth to eyes, mouth to eyes—metal and flint I struck together in hopes of kindling some beauty. I now know it’s a common question asked of ethnically ambiguous young people: What are you? Back then, it scared me. What was I? A face was a map, and mine was unreadable.

In the dark of early morning, I strap on a rubbery white mask embedded with hundreds of tiny LED bulbs that radiate light over my forty-three-year-old face. It glows an ambient red, like a radioactive hockey mask. I put a sign on the closed door to warn my wife away.

Alone in my office, I stare at my phone, watch a muted video of a woman as a long cannula attached to a needle slides under the skin of her cheeks to distribute a solution that stimulates collagen production, the hand jabbing over and over. Her expression is placid, beatific. Growing a new face ought to hurt. One ought to bear it with grace, with pleasure, even.

Twenty years ago, I slid heroin-filled syringes into my arms, my hands, even my toes. On the night shift at the dungeon, I slid needles under the skin of my friends’ nipples or the buttocks of men who paid me; I sewed their testicles with care. I covered myself with tattoos. Since then, many people have asked me: Aren’t you afraid of being an old tattooed lady? I fear death, but I know what mending can be done by puncture, by pain.

Do you use snail mucin? a friend texts me. Applied directly to the skin, the substance is said to hydrate, heal, and reverse the signs of aging. Yes, I text back. Each night, I stare into the bathroom mirror as I smear the mollusks’ slime across my face. I’m a lifelong vegetarian, and I tell my friend that I worry about what happens to the snails. I think they farm them, she says, and the snails live. Later, I repeat this to my wife. You wish, she says.

The first time I got Botox from my dermatologist, I didn’t want the other patients in the waiting room to know why I was there. Them, with their honorable skin checks and cancers and suspicious moles. Insurance didn’t cover what I came for: to erase time. My wrinkles were beautiful, some said, evidence of living, creases that life had folded into me. I wasn’t ambivalent, though. Before I had a wrinkle, I was weary as a god. I was a wizened child on the inside, tired and worried and waking up for school with a gasp. So, yeah, release the crease, erase the evidence of all that weight. Give me back that inch of innocence.

Parked in my driveway, I watch a video of a woman getting tiny holes stamped into her face with microneedles. Her face is still as glass, except for her closed eyes, which twitch as though she’s dreaming.

I look into snail mucin extraction methods and read that some snail farmers soak the mollusks in salts and acids, or poke them with sticks. Nothing I haven’t done to my own face. The least cruel seems one where they allow the snails to crawl around on a bed of mesh in a dark, quiet room. After the creatures are removed unharmed, the farmers squeeze their mucin from the mesh. Still, I decide to stop using it. When this bottle runs out. I don’t believe in torturing animals for beauty (or anything). I only believe in torturing myself.

Before bed, I don my reading glasses and watch a video of a woman having her face zapped with a laser. Her skin reddens instantly, turning the toasty color of broiling meat.

Each night, I squeeze a pea-sized blob of cream onto the back of my hand and spread it across my face. Over time, the outer layers of my skin slough away. I want to peel my face off and see what’s underneath. I want the face I had before I ever smoked a cigarette. I want the face I had before I ever broke my heart. I want the face I had before I knew it was beautiful. I would know what to do with it now.

I watch a video of a woman cutting off pieces of dead skin from her face with a pair of scissors, like dried glue. Her eyes are wide with wonder and repulsion.

As a kid, I used to chew my cuticles until they bled and peel strips of skin from the lining of my cheeks with my teeth. I swallowed all the evidence. The first time someone commented on my scabbed fingers, I made myself stop.

In the movie Face/Off, Nicolas Cage and John Travolta play characters who surgically swap faces. They both do it for revenge, but wouldn’t beauty have been a better motive?

Jane Fonda said she turned to plastic surgery because she “got tired of not looking like how I feel.” I take this to mean she got tired of looking tired, of looking in the mirror and seeing a face she didn’t recognize, a face that didn’t match the way she felt inside herself.

Inside myself, I feel like a rout of snails crawling on a bed of mesh. I feel like a skein of stars cast across the cosmos. Inside, time does not exist. I am still a baby. I am looking in the bathroom mirror and wishing I were dead. I am dead. I am an old woman, my tattoos folded over one another to make new images. I can’t see my child face anymore. I am looking into that ancient face and cupping it in my hands. There you are, my darling, my love.