In Objects of Desire, a writer meditates on an everyday item that haunts them.

Rubber Bands

How can we extend love?

Catherine Barnett

because i’m partial to anything once loved, I peruse the melancholy inventories for sale on Etsy.

I myself have a hankering to be both loved and useful. Useful like this lissome blue rubber band, removed from a bundle of asparagus or broccoli, that I wear here on my wrist in case I need to put my hair up or secure a loosening sole to my sandal long enough to get across Central Park.

What else is desirable when always at hand? Because always at hand? Ubiquity is not generally part of an object’s allure. Usually, it’s the opposite: rarity arousing interest. But the rubber band’s omnipresence may be its allure (that, and the fact that they’re so quiet).

Is it a faux pas to look into a stranger’s eyes and ask his opinion on rubber bands at a cocktail party? How has he acquired his? “They just appear,” he’s likely to say. And disappear almost as easily.

This off-hours research can be an unexpected pleasure, as is dreaming up ways to extend—for inanimate as well as animate objects of desire—what economists call useful life. Rubber bands last longest when stashed in a place without much light or air, though the most lightless, airless location is impractical—what use would they be down there? In the grave. Better to store them in a jar and then keep that jar in the fridge.

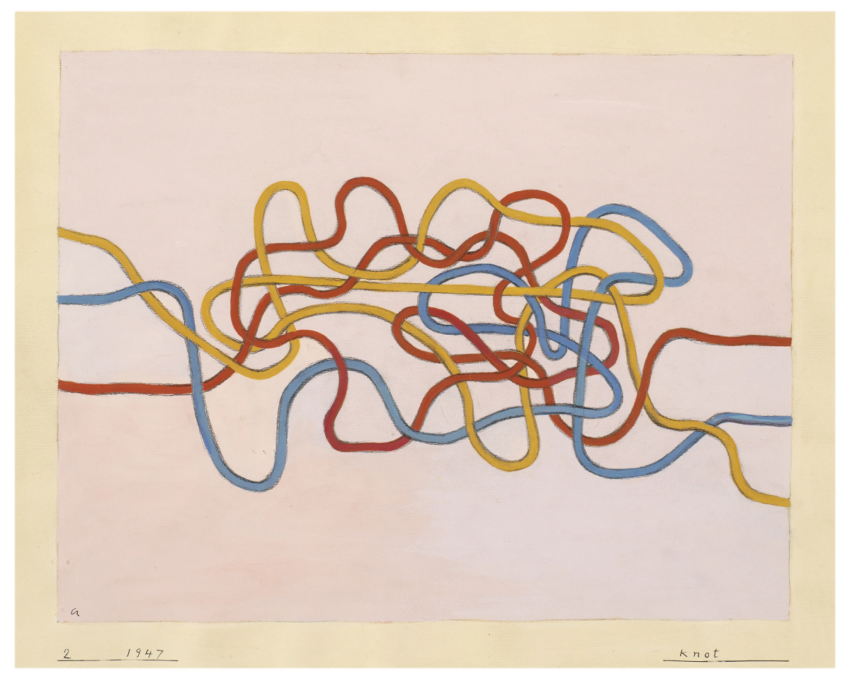

Or bind them one by one into a ball and call it art, which endures. I commend this popular (if sometimes extreme) craze because rubber bands, like those of us endlessly rearranging the fridge, limping across Central Park, and missing each other, have such unpredictable lifespans. Briefer than you imagine when you think it wise, as I once did, to use them to organize a friend’s archive.

The latex in natural rubber bands comes from rubber trees, which can be tapped for up to thirty years before they give out. Like love, the trees are a renewable resource. Rubber bands made from them cannot be easily recycled, but they can be reused. How many times? I don’t know. I only know that when stretched too far, they break.

I keep mine in a bowl next to my vinegars and the twist ties that remind me of my father, as does anything useful.

If desire, that gorgeous life force, is marked by ambivalence, mystery, unpredictability, caprice, invention, misjudgment, and chance, I shouldn’t have been surprised when my feelings for rubber bands became, as the young say of their romantic attachments, “complicated.” The more I learned about them (their carbon footprint, their misuses), the more suspicious I felt. A little let down. A little indifferent. This is a common enough journey: from infatuation to junk drawer. Which isn’t all bad—a junk drawer is a self-portrait, a time machine, a catchall that makes me think of the poet John Ashbery, who, because he never knew what might fly into his poems, liked to keep all his cabinets and drawers wide open.

This morning, I walked to my favorite café, examining the sidewalk for stories as I sometimes do. It seems we have a wayward local mailman who leaves a trail of those thin red loops that the post office orders by the hundred million every year. When they fall to the gray sidewalk, they make a sinuous free-form line. Because I know we share our city streets with the swift paws of Norway rats, the Malpighian tubules of German cockroaches, and surely other humans like me seeking random instances of beauty (not to mention kindness) there, I did not bend to retrieve the rubber bands but left them glowing on the pavement.

Based on my casual field research, it seems the world divides into three camps: those who are blind to this humble accoutrement, those who feel fondly toward it, and those whose ambivalence makes room for the poet Paul Valéry’s observation that “two dangers constantly threaten the world: order and disorder.”

Always in search of more order, I went to the corner hardware store, hoping to diversify and expand my collection. “Try the stationery shop,” the cashier said, to my surprise. I don’t think of rubber bands as office supplies but as tools, like a nail.

To have them at the ready, I keep mine in a bowl next to my vinegars and the twist ties that remind me of my father, as does anything useful. I can see his hands vividly even now, when they are no longer in existence, stretching and twisting a band in a gesture so graceful it’s almost dance. That’s another pleasure: knowing just how much give a rubber band has.

It occurs to me that much of what I toss unthinkingly into my junk drawer—tape, binder clips, string, glue—are simple tools to hold things together. To attach. To be attached by, or to. Which might be another way to fight the second law of thermodynamics, which I’d forgotten about until last week when my mother, who is losing her memory but whose vocabulary is still intact and full of heartbreaking acumen, told me it was useless for me to try to repair her moth-eaten sweaters, which lay in a heap at my feet. “Haven’t you heard of entropy?” she asked.

Nonetheless, I organized the sweaters into separate categories—“cleaned,” “heat-treated,” “repaired,” “need repair”—and swaddled them together using the few rubber bands I could find.

It turns out that rubber bands lose entropy as they’re stretched. When you release them, entropy returns. You can experiment with this at home. Stretch one to its breaking point and press it gently to your lips. You’ll feel it’s warmed. Let it return to its original form and press it again to your lips. It will have cooled.