I hide behind simple things so you’ll find me;

if you don’t find me, you’ll find the things.

—yannis ritsos, “The Meaning of Simplicity,”

translated by edmund keeley

I hide behind simple things so you’ll find me;

if you don’t find me, you’ll find the things.

—yannis ritsos, “The Meaning of Simplicity,”

translated by edmund keeley

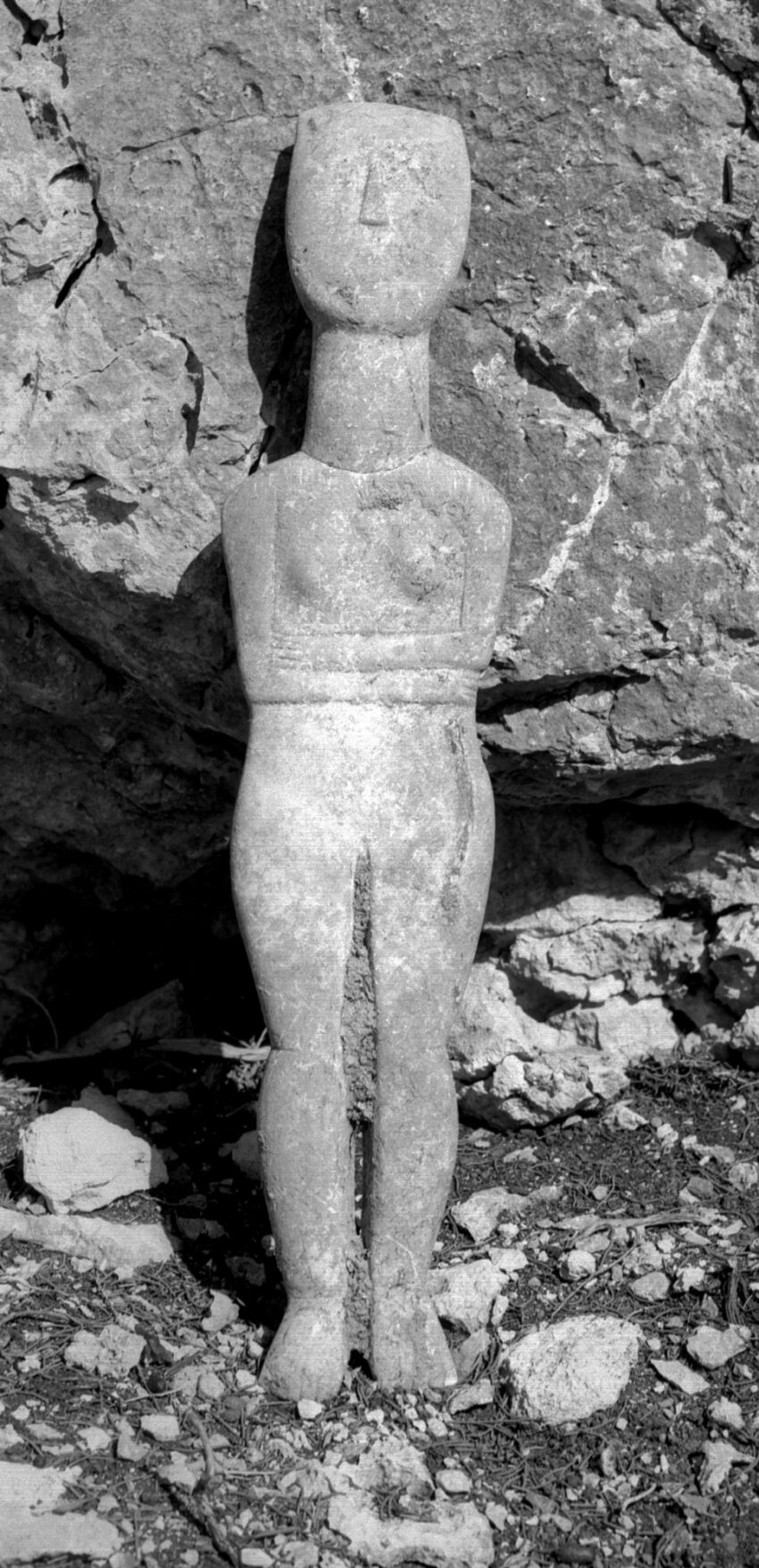

With her small, boxy feet and the stout curves of her calves, her delicately cleft bottom and angular skull, she seems such an odd blend of impervious and vulnerable. Stone and flesh. In a photograph snapped the 1967 day she surfaced on the uninhabited Greek island of Keros, the stylized yet true-to-life female figure looks like she might be the victim of some violent crime. Just which crime remains obscure, as does so much else about her.

Who was she? Who made her? What did she mean to the people who brought her to this remote spot and left her there, exposed to sun, rain, salt, and often ferocious winds? Why and when did they do what they did? And how, if she really was as old as she appeared to be, had she managed to survive, shapely and intact, the last four and a half thousand years?

mysteries surround her discovery too. Inconsistent or partial reports blur slightly the details of how and where one of the young Greek archaeologists in charge of the rescue dig on Keros that late July and early August happened upon this solitary, nearly two-foot-tall figure. Among the largest ever found in a so-called secure context—that is, a site unearthed and documented by recordkeeping archaeologists, equipped with surveying tools, trowels, brushes, sharp pencils, and professional standards—it is also, to date, the only complete sculpture of its kind to have emerged from an authorized excavation on this particular island.

The uncertainty that hovers over the origin of these “Keros” objects makes them not so much outliers as something like emblems.

Though their true provenance will always trail a question mark, Cycladic figurines turn up in museum display cases all over the world, a good number of them “said to be from Keros” or “probably from Keros.” Such dubious attributions are part and shadowy parcel of the site’s mid-twentieth-century ransacking by looters, and—in the terms often used for an earlier, ostensibly more innocent era of amateur Aegean pillage—antiquarians, travelers, enthusiasts, adventurers.

Curious as it sounds, the uncertainty that hovers over the origin of these “Keros” objects makes them not so much outliers as something like emblems, since scholars estimate that of the approximately sixteen hundred Cycladic figurines that make up the corpus, as many as 90 percent come from doubtful sources. We don’t know where they were fashioned, what other things or structures once accompanied them, how they made their way into and out of the ground—or whether they’re even real. (Fakes abound in this decidedly insecure context.) We will likely never know. Which for some reason makes me want to dig deeper.

when i’m asked what I’m writing these days and I say, “It’s about Cycladic figurines,” I usually get a blank or confused look. “Socratic figurines?” one friend seems embarrassed to admit that she has no idea what I’m talking about. “Schizophrenic figurines?” another tilts her head and wrinkles her nose quizzically. “Synthetic?” wonders another.

Cycladic—I then hear myself intoning, maybe pedantically—from the Cyclades: that constellation of 220 islands of drastically variable size and situation to the southeast of mainland Greece. And the figurines…you might not know what they’re called, but you’ve probably seen them—sleek, naked women with empty faces, triangular noses, and elongated necks. Their arms are almost always crossed like this, left over right…I stiffen my spine and demonstrate. Many are less than four inches tall. A few are male, or androgynous…

Such explanations don’t begin to account for why I find these objects mesmerizing.

the moment of encounter between the modern excavator and the ancient object passes unmentioned in published reports of the 1967 Keros investigations. But it grips me. What, I wonder, did Photeini Zapheiropoulou feel when she first registered this strangely tender figure “lying carelessly abandoned in the soil,” as an early version of the events has it? Delight? Awe? Confusion? A flicker of female disquiet at the sight of that bare, prone form?

Not that this quick-to-laugh, cigarette-smoking, brandy-swigging, piano-playing, trouser-wearing Athenian cosmopolitan and polyglot twentieth-century employee of the Greek Archaeological Service had much in common with the weathered marble artifact besides certain body parts. Did that hardly scientific but undeniable fact color how Zapheiropoulou thought about the rare whole sculpture she’d encountered “with the head placed on the ground among blocks of rock,” as she described it years afterward? She wasn’t just a woman codirecting an otherwise all-male dig; she was one of the very few women present on this isolated and basically desolate island.

The picture of the facedown figurine suggests contrivance. In a more obviously staged image from around the time of the statue’s discovery “beside a feature resembling the opening of a natural cavity,” she stands propped against a rock, her rounded hips, girlish breasts, and carefully incised pubic triangle turned directly toward the camera. To me she looks a bit reluctant to participate in the full-frontal photo shoot as she clutches her middle that uneasy way.

“For reasons of safety,” one of Zapheiropoulou’s later accounts concludes, inconclusively, “the excavation stopped at that point.”

what purportedly happened next almost sounds like a scene snipped from an old-timey, swashbuckling black-and-white movie.

That night, alone in her tent pitched on the Keros shore—so Zapheiropoulou writes in a rollicking memoir set down in much older age—the archaeologist wedged the bulky statue under her pillow, alongside a long, sharp knife. Even with the dig’s ax-wielding watchman posted just outside the flap, “the kind of sleep I had,” she sums up those fitful hours, “I don’t need to describe.” In the morning, there was a great fuss as a contingent of uniformed officers sailed over from the much larger island of Naxos to escort the figurine and its finder to the police station in the bustling port some twenty miles off.

After Zapheiropoulou relinquished it, the precious item was transported under armed guard to the nearby archaeological museum, then just a few cramped rooms housed in the main town’s gymnasium. According to one contemporary visitor, the space was “extremely small and seldom open.…In this museum there are no labels and no information. None of the finds have been published. There are no dates. One is left with the things themselves, matchless creatures.”

Eventually tagged with the humdrum number NM4181, it—she—would move in a few years, when the museum relocated uphill to a cavernous Venetian mansion perched toward the top of the labyrinthine medieval warren that comprises the old town. And so she remains upright in her vitrine on the afternoon decades later when I come to pay her a call. In person, she looks to me less like a victim, more like a kind of prehistoric prisoner, confined to a present-day plexiglass dock.

Who was she? Who is she? Her arms pulled tight across her marble chest, she isn’t talking.

and yet, like the other figurines of her kind that have come to be seen as near-metonymic embodiments of the whitewashed Greek islands, she does somehow speak across the ages.

We can peer at her and—despite her impassivity, her antiquity—glimpse something of ourselves.

She predates by thousands of years the Parthenon, Plato, Sophocles, Homer, the Buddha, and even, by half a millennium or more, the Minoans, the Mycenaeans, and estimates for both the biblical Exodus and the composition of Gilgamesh. Still, she seems strangely familiar. This isn’t just a function of how modern or, really, modernist she looks—the way she suggests the work of artists like Modigliani, Picasso, and Giacometti, who took inspiration from the sparely supple preclassical abstraction of Cycladic figurines like her. (“I’m sure the well known Cycladic head in The Louvre influenced Brancusi, & was the parent of…that simple oval egg-shaped form he called ‘The Beginning of the World,’” the British sculptor Henry Moore scribbled in a 1969 letter.) These modern makers, too, were responding to the immediate force of the objects’ presence, and to carving that feels at once out of time and intimate—elemental yet clearly shaped by human hands. There’s an eerie expressiveness to the figurines’ lack of expression, which renders them something like Rorschach tests in stone. We can, that is, look at a sculpture like NM4181 and see any number of things. We can peer at her and—despite her impassivity, her antiquity—glimpse something of ourselves.

Not that we understand any better now who NM4181 is than Zapheiropoulou did when she stumbled across her almost six decades ago. Since that time, the archaeology of the Cycladic islands has grown appreciably more rigorous, exacting, and scientific, as several generations of specialists have engaged in state-of-the-art thermoluminescence dating, photogrammetry, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, and other such technical approaches to decoding the physical traces left behind by a long-gone preliterate culture. For all the precisely charted data they’ve amassed, though, the experts themselves can only speculate about what these sculptures might have represented to the people who chiseled them and first held them dear.

Perhaps NM4181 is a human likeness. She could be a goddess, or a nymph. She may once have functioned as a household saint, a tutelary deity, a magical, evil-eye-averting device—or a status symbol. A communal symbol. Did she serve as an attendant or concubine believed to ease a dead man’s journey into the afterlife? Fertility aid or marmoreal midwife meant to protect a woman during pregnancy and labor? Sepulchral object? Everyday object? Maybe she was an outsize doll. “Many theories have been advanced,” writes one of the leading authorities in the field, “all of them arbitrary.”

That said, the Cycladic sculptures don’t just belong to the third millennium b.c.e. They continue to exist in our world today, and they continue to mean things and matter in a major way to the radically different people who’ve faced off with them over the years. These people are as various as their attitudes toward the figurines: archaeologists and artists, yes, but also islanders, collectors, looters, tourists, scholars, politicians, conservators, customs agents, dealers, and, of course, those ever-enterprising forgers intent on replicating the originals’ aged texture and patina with the help of furniture varnish, coarse-grained sugar, and hydrochloric acid.

How we understand what these figurines are, were, or are alleged to be depends, in other words, very much on who we are and on the multitudinous ways that we, in the present, make sense of the past, in all its broken pieces.

no matter what she did or didn’t commit to writing afterward, Zapheiropoulou must have recognized right away the exceptional and exceptionally weird (if alluring) nature of the complete figurine. All the other relics she and her crew had gathered up in the course of their few weeks on Keros had been fragments, and miniature ones at that: 174 tiny heads, torsos, legs, and pelvises of diminutive feminine forms, as well as a vast quantity of marble and pottery shards—artifacts, she’d recount, “more numerous than the stones…that were removed to find them.”

Most evenings that summer, she and the workers would heap these fragments into large wooden crates, which they’d load onto a fishing boat to be ferried without fanfare to Naxos and its extremely small and seldom open museum.

But she was far from the first to have noticed the fragments scattered across the western shore of Keros, or the island’s own profound weirdness, its allure.

it’s a cycladic game of connect the dots: the much-heralded marble head at the Louvre that Henry Moore said inspired Brancusi appears in the museum’s inventory as coming “from the island of Keros, where it was found in a grave by the Mayor of Amorgos, who offered it to O. Rayet, and he donated it to the Musée du Louvre in 1873.” Amorgos is a large island close to the miniature chain-within-a-chain known as the Small, or Lesser, Cyclades. In the nineteenth century, its dramatically cliff-hanging, medieval Panagia Chozoviotissa Monastery owned and used neighboring Keros for grazing land; a few shepherds and their bleating flocks counted as the “minor” island’s only regular inhabitants. O. Rayet was Olivier, a French archaeologist who spent time digging in Greece and often acted as an agent for European museums. This is the first official mention of Keros as a “findspot” for a figurine or fragment.

keros is itself a fragment—one of a wider scattering of seemingly broken parts, which, combined, make up a whole.

If on modern maps the Cyclades look strewn rather randomly across the Aegean, the ancient Greeks saw order in this seascape. They saw the Kykládes as a kýklos, a circle radiating nautically, cosmically, and mythically around the small, sacred island not of Keros but of Delos, “ranged like a chorus, / and not quiet or noiseless but ringed with sound,” in the words of the third-century-b.c.e. Alexandrian poet, philosopher, and librarian Callimachus. Delos, however, was no unwobbling pivot. In antiquity, the island was believed to have floated from place to place, “tossed by the…blasts of all manner of winds,” as the fifth-century-b.c.e. lyric poet Pindar put it (in yet another kind of fragment). It finally came to a halt and set down roots when Leto, pregnant by Zeus and stalked by his jealous wife, Hera, gave anguished birth there to Apollo, god of the sun and sundry other things. Throughout the difficult divine delivery, a flock of swans (“the Muses’ birds”) circled the island seven times, singing—till Apollo leaped forth in a great burst of light, the local nymphs chanted, the sky echoed their hymn, olive trees and lakes gushed gold…and where she stops, nobody knows. “If so many songs circle round you,” Callimachus asked Delos itself, “what kind shall I weave about you?”

Keros has since become a constant in our lives, a silent, striking backdrop to our evolving being.

But all those circles and all that gold are only one piece of this insular puzzle, and ancient is, again, a relative term. These sophisticated classical poets and the inky circuits they composed around Apollo’s birthplace belong practically to recent history, at least compared with the Bronze Age islanders who created and first possessed what we now call “Cycladic figurines.” We have no idea, meanwhile, how those islanders referred to their islands, let alone their figurines. We don’t know what language they spoke. We can’t say whether Delos played a role in their beliefs or had a place on their mental maps. How long, I wonder, might the memory of such things have persisted? And could an inveterate civilizational cataloguer like Callimachus, writing some two millennia after the demise of Early Cycladic culture, have answered those questions? Among his own many lost works are one tract titled On the Founding of Islands and Cities and Changes of Names and another, titled Curiosities Collected All Over the World According to Place.

Whatever name the Cyclades went by in prehistory—that time not before time but before written history—their constituent parts were and are linked by much more than myth. Some eighteen thousand years ago, they formed a single large landmass with a few adjacent islands. They still do, though the valleys and lower slopes of that landmass have been swallowed by the rising waters, so that all we now see poking up are the peaks of its mountains, which look to us like distinct islands…as the ferry pulls into port after port and we lean over its painted white railing to peer down when a sailor in darkly worn coveralls hurls a thick rope to the dockworker poised to grab it and loop it over the stubby iron post on the quay…and we watch the long line of exhaust-spewing trucks, cars, and motor scooters; the hordes of tourists hauling backpacks or pulling suitcases; the locals with their bundles, boxes, and bags—everyone awaiting their cue to surge forward and swarm onto the boat that will, with a blast, push off in just minutes and carry them, carry us, from one island to the next, from Syros to Paros to Naxos to Ios…

Or is it in fact all one?

i don’t remember our first glimpse of Keros. That is, I can’t pry one distinct initial impression apart from the thousands that came later. And glimpse isn’t really the right word for what P. and I have done with our eyes for the quarter century that we’ve returned every late spring or early autumn, our work and bathing suits in tow, and sat reading or scribbling, sipping, nibbling, or just staring out from the balcony of the same small room on the minuscule unfamous island that faces directly onto the quietly astonishing sight of its chalk-and-ash-gray, maquis-stippled hills.

We’d never heard of Keros when we first made our way to “our” island, opposite. It was early one September, and we craved a little time away from dusty, angry Jerusalem, home though it was. We needed not so much a vacation as an extension—of our sight lines, our muscles, our sense of ourselves as living in the wider region, beyond the ever-heightening national walls.

Keros has since become a constant in our lives, a silent, striking backdrop to our evolving being. As we come and go and change, as “our” minuscule island changes (it’s no longer exactly unfamous, alas), the view of Keros seems to stay the same—modest yet commanding, immutable yet oddly animate.

Keros is always there. As we write and swim, walk and talk, eat, sleep, dream, it looms mutely. In the watercolors I often paint while perched on that shaded balcony, Keros appears with a frequency that startles me when I flip back through a pile of old notebooks. I wasn’t conscious of having fixated on its outline so, though as I look now at my multiple approximations of its subtle peaks and endlessly intricate coastline, the urge to keep trying to capture it over the years seems less compulsive than predictable: Keros simply dominates the landscape of the much lower, gentler dot on the map that we’ve come to consider “our” island (“a birthmark in the Aegean,” P. calls it). Keros is by far the most pronounced—and dramatic—landform that we see when we look up and out. Of course I keep trying to paint it.

And even when we’re not squinting at it as actively as I am when I attempt to coax some loose likeness of it from the little blocks of pigment in my plastic set, it hovers always in our peripheral vision, like a persistent memory—though as I write that, I wonder: Of what?

Translations of Callimachus from Hymns, Epigrams, Select Fragments, by Stanley Lombardo and Diane Rayor, and Hecale, Hymns, Epigrams, by Dee L. Clayman. Translations of Pindar from Strabo’s Geography, by Horace Leonard Jones. The piece is excerpted from Cycladic: An Excavation in Fragments, due out in 2027 from Yale University Press.

Become a Sustaining Subscriber and help us stay in print. Four issues per year, plus our Virginia Woolf–inspired candle and new tote.

Become a Sustaining Subscriber and receive four print issues per year, plus our Virginia Woolf–inspired candle and new tote.