There he stands now, and it’s either him or his brother. It’s him. It has to be him. You can tell by the clothes, the posture, the glances he casts at the station clock. His brother would never try to disguise his height by shifting his weight onto one leg and pushing the other slightly out in front. His brother would never feel this anxious just because someone was a little late. That’s something only he would do, he who is not his brother, he who stands there on the platform and has just calculated that fifteen minutes is nine hundred seconds and nine hundred seconds is nothing.

He takes out his phone and dials the number for the fifth time. He stares straight ahead, listening to the ringtone. Then he hangs up and goes to sit on a bench, his rolling suitcase upright beside him like a well-trained dog. The minutes pass. He thinks about how many times he’s sat at a train station waiting for his brother. Sat at a café waiting for his brother. Stayed awake waiting for his brother. Because this was when they were supposed to meet, right? A second of doubt. We said…? Or did we say? No, they were definitely supposed to meet right here eighteen minutes ago. He’s sure of it.

Trains arrive, trains depart. The family with matching luggage leaves. The two tanned men with ski bags stand up. He who is not his brother remains seated. City names tick upward on the departure board, the loudspeaker announces delays, passengers groan and exchange weary looks. But he who is not his brother meets no one’s gaze. He looks down at his phone and thinks: Twenty minutes. Twenty minutes is nothing. Not twenty-five minutes either. And thirty minutes is only eighteen hundred seconds, and a brother being eighteen hundred seconds late is completely normal. His brother isn’t tied up in a basement or unconscious in a forest. He hasn’t slipped on an icy escalator and cracked his skull on a jagged step. His brain is not leaking from the back of his head.

People say they look alike. Maybe they do. They must, because sometimes strangers come up and greet him. They say, “Thanks so much for the help with the tarp,” or “Didn’t you study philosophy with Julia?” And now a dark-haired girl approaches, takes out one earbud, and says (a little too loudly), “You killed it on the dance floor Saturday night.” “Thanks,” says the one who is not his brother. “But you must be confusing me with my brother.” The girl looks a bit strange and apologizes, and he who is not his brother says, “No worries, I totally get it, we look insanely alike.” On her way to the café, she puts her earbud back in, and he who is not his brother stays seated. “Thanks,” he should have said. “Wasn’t it a great party?” Instantly he becomes his brother. “Wasn’t it a great party and where are you traveling and shouldn’t we grab a coffee?” The girl nods and takes out her other earbud, and they get in line and talk about the snow and delayed trains and where they spent Christmas, and the cashier has to clear her throat for them to stop talking and order.

He who is suddenly his brother orders a cappuccino instead of a drip coffee and impulsively buys two or three sweets without thinking about the price and pays for both him and her without the slightest worry that he’s done something wrong. He doesn’t think maybe he should’ve let her pay or they could’ve split the bill or he could’ve paid for the sweets and she for her coffee. Soon they’re sitting on opposite sides of the café table, and the threatening junkies by the lockers disappear, and he stops keeping an eye on his suitcase. He forgets about time for several minutes.

Now when he laughs, he feels it rather than observes it, and when she licks her spoon he doesn’t get irritated, and if it gets quiet (which it doesn’t) or if she shows signs of wanting to catch her train (which she doesn’t), he doesn’t ask any of his trick questions to prove they’re not meant for each other (“By the way, which Borges novel is your favorite?”). Instead they talk about New Year’s and firework phobias, and she tells him about the guy who showed up to a costume party not in costume and how pissed he got when people guessed he was a PE teacher. And he tells the story of the time he invited his brother to a costume party. “I was dressed as Zorro and my brother as an orc, with an elaborate rubber mask that smelled sweet like candy on the inside, a papier-mâché flail, and chain mail made of key rings. I remember my brother’s panicked look when he saw all the cigarette holders and monocles, how he ripped off the mask and tried to hide the flail behind his back, and all evening he was sort of outside his body, like he always gets when things don’t go how he’d planned,” says he who is his brother to the girl across the table.

It’s evening and she’s missed her train, and instead of going home to celebrate New Year’s with her family, they end up at a stranger’s apartment where she knows everyone and he knows no one, but since he’s not himself, they barely make it past the sea of shoes in the hallway before he starts greeting people. He hugs instead of shaking hands and drinks juice instead of chugging wine. He tells funny stories about his ex-boss’s tattoos. It’s he who stands on the dance floor in his black cape while his brother sneaks out onto the balcony in his rattling chain mail and looks in through the foggy windows, counting the seconds until someone notices he’s gone.

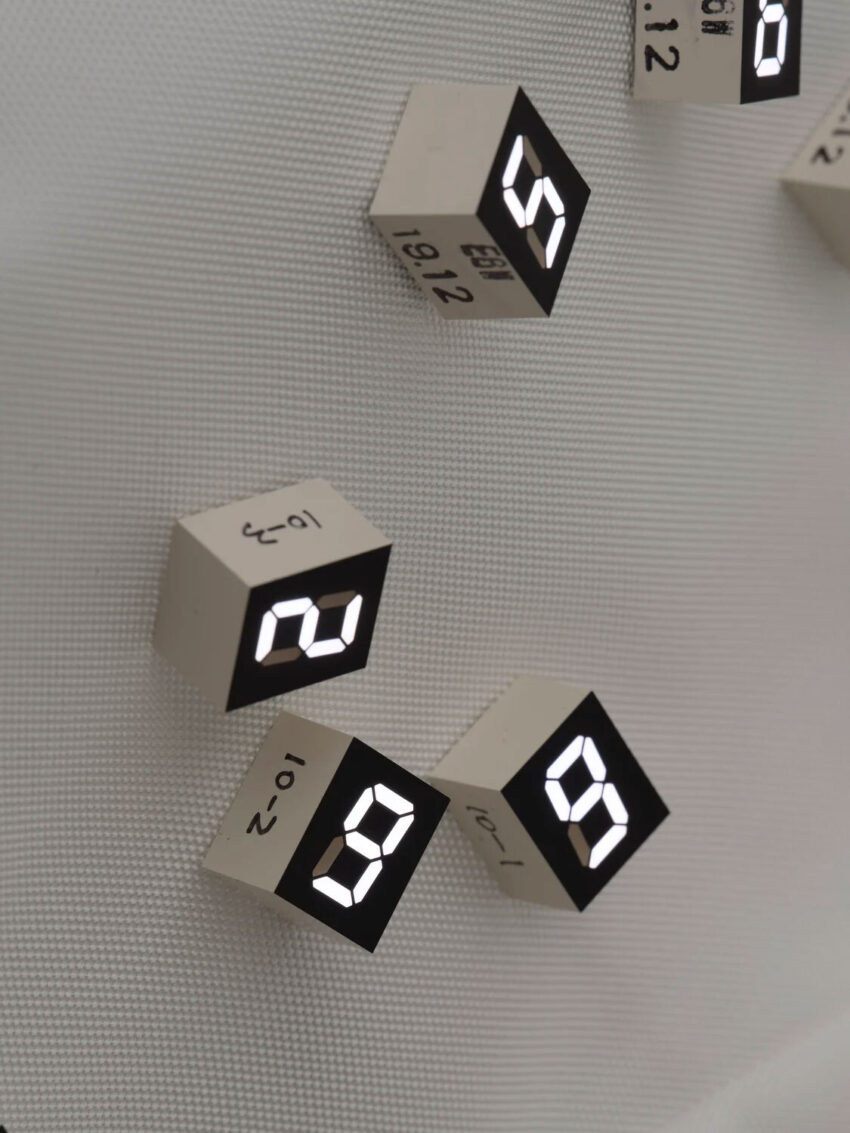

He who is not his brother remains seated on the bench, checks the station clock, and thinks: Thirty-nine minutes. Thirty-nine minutes is nothing. Especially compared with his age, which is thirty-one—no, thirty-two—years. And thirty-two years is 11,680 days, which is 280,320 hours, which is more than a billion seconds. A billion seconds minus forty-one minutes minus twenty-four or twenty-five years, because he must have been seven or maybe eight when it started.

The digital watch was black and plastic and waterproof to a depth of twenty-five meters (though it fogged up every time he showered). The stopwatch function was activated with the thin metal button on the side, and on the first day he timed which route to school was fastest. Exactly how many seconds did you save by crossing Hornsgatan instead of taking the underpass? (Eighteen to twenty-four, depending on the weather.) How many seconds did you lose by taking the bridge over Långholmsgatan? (Four to twelve, depending on the lights.) How long did you have to wait in the bathroom before they gave up? (Twelve to seventeen minutes, depending on whether it was breakfast or lunch break.) He wrote down his observations in a special notebook. The time it took for the red pedestrian signal to turn green (sixty-eight seconds, regardless of whether you pressed the button). The time it took to peel an orange (forty-five seconds with fingernails, eighty-five with Dad’s spiral technique). The time it took for Mom to stop crying after a phone call (ten minutes without comforting, thirteen with comforting—which always made him unsure whether or not comforting was a good idea).

Everything could be measured. The time it took for Dad to promise he’d soon send his new address (four and a half seconds). The time it took the elevator to crawl from the ground floor to the fifth floor (twenty-two seconds). The time it took to go through all the junk mail in search of at least one postcard (three and a half minutes).

The only person who existed outside of time was his brother. His brother laughed at time, pulled it aside and stuffed it with snow, hoisted it up a flagpole and pointed at it so that everyone laughed.

Deep down he knows that nothing has happened. His brother’s frozen body isn’t struggling to get out of an icy lake. His brother isn’t trapped under a bus on Sveavägen. His guts aren’t glittering red against the white snow. Any moment now, his brother will come walking through the revolving door. And when he does, I’ll demand my time back, thinks the one who is not his brother. Ten hours for all the times he was late. Thirty hours for all the movies I watched just because he liked them. And one hundred—no, one hundred and fifty—hours for all the times his shut-off phone made me worried.

What else? Three weeks for all the times I made up that Dad had called when we were little. One month for the postcards I sent in Dad’s name. Half a year for all the times I explained that things happened for a reason. And eighty-nine minutes—no, ninety minutes—for the time I’ve waited here today.

And just then, or exactly twelve minutes later, the blurry silhouette of he who is his brother comes running through the revolving door of the train station, his scarf fluttering behind him. He squints like he does when he’s not wearing lenses, and as soon as their eyes meet, his face lights up. He stretches out his arms, and it’s only when they’re holding each other that his brother understands what’s about to happen. They stand there for ten seconds, half an hour, three or four years, and he says don’t cry, and I didn’t cry, I just stood there, holding him, not wanting to let go.

Newsletter

Sign up for The Yale Review newsletter to receive our latest articles in your inbox, as well as treasures from the archives, news, events, and more.